Seagrass the wonder plant!

Did you know that there are flowering plants that live in the sea? The unique characteristics of seagrasses are vital for the health of our planet.

Every tide tells a story. Discover how waves, shells, and even litter reveal clues about marine life and our shared connection with nature.

We love visiting sandy beaches for fun and relaxation, but have you ever stopped to think about how they connect us to the vast ocean? These dynamic ecosystems are a crucial link between the land and the ocean, and they have a lot more going on than meets the eye.

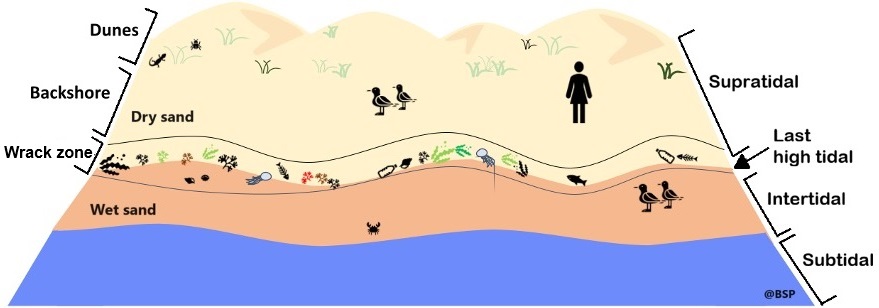

Sandy beaches are coastal areas made up of loose sand and small rocks. They comprise more than one-third of the world’s shorelines and occur from tropical islands to polar regions.[1] A sandy beach is divided into several zones (figure 1), each shaped by how often it is washed by tides and waves. Closest to the ocean is the subtidal zone, which always remains underwater. Above it lies the intertidal zone, regularly covered and exposed by waves and tides. The wrack zone marks the highest reach of the tide, where natural debris and human-made objects accumulate. Further up on the beach, the backshore is rarely touched by the ocean water and thus stays mostly dry. It connects the beach to the dune zone, where vegetation takes hold and helps stabilize the sand.

Waves and tides constantly move the beach sand around, which means the beach is an ever-changing, dynamic environment. This constant motion not only changes the shape of the beach but also brings objects that provide clues about the health of the ocean and its inhabitants.

When the tide recedes, the ocean leaves behind a variety of organisms and objects. These are said to be ‘stranded’ on the beach, mainly in the wrack zone (figure 2) . During a beach walk, you might spot shells, which are the remains of mollusks that live in the intertidal zone or just below the waves.[2] Occasionally, larger organisms such as jellyfish, sand dollars, or even whales may also wash ashore. Each of these strandings provides valuable clues about marine life and ecosystems.

Egg capsules of sharks and rays (figure 3), for example, can reveal which fish species inhabit nearby waters and whether the area serves as an important breeding ground. Finding large amounts of seagrass may signal the presence of a nearby seagrass bed,[3] while bits of coral can indicate a coral reef in the subtidal zone in front of the beach.

Most strandings are a natural part of the ocean’s life cycle. Many of these organisms die in the water from natural causes such as old age, storms, or predation, and are carried ashore by waves and currents. Although piles of seaweeds, seagrass, or dead animals may seem unpleasant to beach visitors, these strandings are vital resources for many sandy beach organisms.

Sandy beaches are unstable environments, so only very few plants can grow there excluding the more stable dune zones. This means that primary productivity, i.e. the process of converting light or chemical energy into food, like photosynthesis in plants, is low. Many beach organisms therefore depend on organic material brought in by the waves, such as seaweeds, dead animals and other debris, which serve as an important food source.

Sometimes, however, huge numbers of organisms wash ashore all at once. Scientists call these extreme events ‘mass strandings’. These mass strandings can be warning signs that something unusual is happening in the ocean, such as storms, pollution, or disease.

The number of individuals involved in mass strandings varies widely, from a few large animals, such as dolphins or whales, to hundreds of millions of small invertebrates. For example, over 100 million by-the-wind sailor jellyfish (Velella velella) were stranded on the west coast of New Zealand in 2006, likely driven by warmer temperatures (which boost jellyfish abundance) combined with stormy weather.[4]

Massive seaweed strandings are becoming more common worldwide (figure 4), often linked to nutrient enrichment, climate change, and shifting ocean currents. In Europe, green tides caused by blooms of Ulva seaweeds have affected the Atlantic coasts of France since the 1970s, with annual strandings exceeding 100 000 tons.[5] In the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, golden tides of floating Sargassum have blanketed beaches, burying shorelines, threatening turtle nesting sites, as well as disrupting tourism and fisheries.

Unfortunately, not everything that washes ashore comes from nature. Almost every beach in the world now contains marine litter, which includes waste from human activities such as plastics, metals, and glass (figure 5). This is a clear reminder that what we do on land has a direct impact on the ocean.

Human-made litter, such as plastic and chemicals, can seriously harm beach animals that may eat or become entangled in this debris. Pollution also makes beaches less appealing to visitors and can damage local economies that depend on tourism.

For centuries, people have walked along the shore collecting objects carried by the tide, an activity known as beachcombing, which has connected cultures across continents.

Indigenous peoples in Canada and Greenland, for example, were familiar with iron long before direct contact with Europeans. The likely source of this metal was driftwood with embedded nails that had floated across the Atlantic from European shores. Long before telephones or the internet, messages in bottles also crossed oceans, sparking curiosity about distant places and people.

The distance that stranded objects travel depends on their buoyancy. Light materials, such as plastics and seaweeds (particularly Sargassum), can float for long periods and be carried great distances by ocean currents, sometimes across entire oceans. On the other hand, heavier objects such as metal, shells, and coral skeletons usually sink or move only short distances, suggesting that they originated near the beach at which they are found.

Sandy beaches are much more than piles of sand or places for recreation. They are dynamic ecosystems that connect land and ocean, past and present. The next time you walk along the shore, take a closer look at what the ocean leaves behind: shells, seaweed, or even litter. Each item tells a story about life beneath the waves and the many ways humans and nature are connected.

See the companion Teach article for classroom activities at a sandy beach.

This is contribution 163 from the Smithsonian’s MarineGEO and Tennenbaum Marine Observatories Network.

[1] Luijendijk A et al. (2018) The State of the World’s Beaches. Scientific Reports: 6641. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24630-6

[2] Korn A (2016) Opening seashells to reveal climate secrets. Science in School 35: 12–4.

[3] Crouch F (2024) Seagrass the wonder plant! Science in School 67: 1–6.

[4] Flux JEC (2008) First mass stranding of Velella velella in New Zealand. Marine Biodiversity Records 1: e84. doi: 10.1017/S175526720700872X

[5] Charlier RH et al. (2008) How Brittany and Florida coasts cope with green tides. International Journal of Environmental Studies 65: 191–208. doi: 10.1080/00207230701791448

This article is of great interest because, starting from a generally familiar and appreciated environment (the sandy coast), it provides a useful contribution to our knowledge of this environment beyond the aspects related to tourism and leisure.

It also serves as a valuable introduction to subsequent lessons on marine environment within various disciplines (biology, Earth sciences/geography, chemistry, environmental sciences).

It can also be used to discuss socio-scientific issues related to the sustainable management of the marine and coastal environment.

Giulia Realdon, University of Camerino, Italy

Did you know that there are flowering plants that live in the sea? The unique characteristics of seagrasses are vital for the health of our planet.

Turn a beach visit into a science adventure! Explore the animals, plants, shells, and even litter stranded on the beach to reveal the secrets of marine life and ocean dynamics.

Looking for a user-friendly interactive map-based educational tool on the ocean? Dive into the European Atlas of the…