Supporting materials

Tables 1 and 2, Worksheets 1, 2 and 3 (Word document)

Download

Download this article as a PDF

Friedlinde Krotscheck describes how she used a cutting-edge science article from Science in School as the main focus of a teaching unit on the human body.

For teenagers, school lessons can be of secondary importance. Many students are interested principally in their appearance, their partners and having a good time outside school; they are also very sensitive to the opinions of their peers. When I reviewed an article for Science in School about a new potential hormone therapy for obesity (Wynne & Bloom, 2007), therefore, I wondered whether I could use the article and the concerns of teenagers to get my Year 10 students (ages 15-16) more involved in their biology lessons.

The first semester of Year 10 is dedicated to ‘the human body’; this is the first and only time the students look at the topic in depth. Over three months, I devoted all 24 biology lessons (45 minutes each) to the sub-topic of ‘homeostasis and the human body’, focusing on the Science in School article, supplemented with video clips from The Science of Fat lectures (Evans & Friedman, 2004).

I began by asking my students if they would like to try a different teaching approach, based on a folder I had prepared containing worksheets and tables. The students would work independently and in groups to develop their own portfolios of information (notes, diagrams and essays), present their results to the others and take part in class debates. The students responded enthusiastically to the idea.

During the next three months, the students’ enthusiasm for both the topic and the teaching approach continued. They were motivated to study the organ systems, grasp the principle of homeostasis and critically analyse their own lifestyles. I was impressed at how hard they worked on their portfolios – also outside lessons – and at their eagerness to learn more about the science involved, to influence the direction of the teaching unit, to teach each other and to discuss the ethical issues involved.

Of course, when addressing the topic of obesity, one concern is how to deal sensitively with any overweight or obese students in the class. Because the teaching unit began with a fairly lengthy consideration of homeostasis and metabolism, the students were quite relaxed by the time we discussed body mass index – and of course the students’ individual data were not made public.

Once we started discussing obesity and the research article, my two overweight students were elated, realising that their condition was not necessarily their fault – and began to discuss their eating habits openly in class. Other students talked openly about other weight problems, including anorexia and bulimia.

Below are guidelines for reproducing the teaching unit. I used it to introduce (with the students’ agreement) a different approach to biology lessons, similar to the way scientists work. It also made my students realise that basic factual knowledge is important for understanding cutting-edge research.

If you are not able to devote such a long time to the topic, you could just use small parts of the project, or individual worksheets.

Start the first lesson with the simple question “How are you?” Discussing the students’ answers and separating them into polite answers and honest reflections of their current state of emotions (e.g. sad, happy, tired, bored) should lead to factors that influenced their answers, for example:

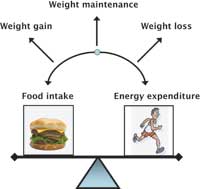

From there, lead the discussion on to human metabolism and one of the diagrams (the energy balance, right) from Wynne & Bloom (2007). As homework, the students should complete Table 1 each day for a week, listing what they eat and what exercise they take. All tables and worksheets needed for the unit can be downloaded from the Science in School websitew1.

| Food Intake | Energy Expenditure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day | Food description | ml or g | Activity | Time | Distance |

To address the topic of metabolism, the students need to understand the organ systems of the body and how they work together to maintain homeostasis. Over the course of the whole unit, the students should gather a portfolio of information about the diverse functions of the organ systems, working either in groups or individually, in the classroom or at home. It is important that the teacher is only the provider of materials (textbooks, websites, models, diagrams and other information about the different organ systems); the students should gather the facts by themselves. I gave my students very little guidance about which facts to collect – providing support mostly for the weaker students. Other teachers may prefer to provide more structure.

Each group of students could concentrate on one organ system and then give a 15 minute presentation, providing their audience with a quiz to complete.

Once they have collected information about all the organ systems, the students should use Worksheet 1 to:

I spent 12 lessons on the first two parts of the teaching unit, after which my students had a basic understanding of the organ systems, how they depend on each other and what homeostasis is. The only teacher lecture I gave was about the central nervous system; otherwise all the topics were student-led.

Referring to their data in Table 1, the students should each state a hypothesis about their own energy balance (e.g. weight loss or weight gain). They should then consider how their results can be compared quantitatively to those of their classmates – and arrive at the idea of using the body mass index (BMI).

BMI = body mass (kg)

(height (m))2

Using the equation or an online BMI calculatorw2, each student should calculate his or her own BMI. The first of The Science of Fat holiday lectures (‘Deconstructing obesity’ by Jeffrey M Friedman) can be used to introduce some of the limitations of BMI, in particular that it does not apply equally well to everybody.

Then, using Table 2 and the data from Table 1, each student should calculate his or her energy balance each day and average the data over the week to see in which direction his or her energy balance tips. To do this, the students will need the teacher’s guidance to convert the data in Table 1 into kilojoules. There are also many websites that do the calculations or provide the necessary informationw3.

| Food intake minus energy expenditure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Day | + kJ (food intake) | – kJ (energy expenditure) | Energy balance |

The calculated energy balance will vary from student to student – and may differ from the hypotheses made at the beginning of this section. On the ‘energy balance’ diagram (see above), fill in the energy balance (in kJ) calculated for each student and discuss the results. The students will realise that total energy expenditure can be divided into the energy that the body uses for metabolic processes when at rest (our basal metabolic rate) and the energy used during activity. However, Table 2 only includes the energy expenditure during activity – and the basal metabolic rate will vary from student to student.

Our metabolic energy expenditure can be estimated, based on our height, weight, sex and agew4, w5. The students could estimate their basal metabolic rate and include it in the calculation of their energy balance in Table 2. How does this change the students’ position on the ‘energy balance’ diagram (see above)?

At this point, metabolism at the level of the cell can be introduced using Worksheet 2. The students should use their textbooks to answer the following questions, making the connection between our own energy balance and the activities of the cells, tissues and organs.

Among my students, this led to a discussion of the fact that our phenotype – for example, whether we are tall or whether we are fat – is affected by how the cells in our organs function. Sometimes these cells are present but they do not function properly. My students then concluded that homeostasis happens at all levels – between cells and between organs – and that homeostasis (balance) is necessary for a healthy body.

Even if the variation in metabolic energy expenditure were taken into account, not all the students would have an energy balance of close to 0; instead, some of them clearly consume more (or less) energy than they expend. Why? The discussion should lead to the concept of satiety: the feeling of having eaten enough.

Introduce a second diagram (right) from Wynne & Bloom (2007) – but without labelsw1. Describe the research reported in the article and explain the signalling involved in appetite, eating and satiety. In particular, the role of the L cell can be researched and discussed, drawing on the students’ knowledge of cell functions within our organ systems.

The students should label the diagram accordingly.

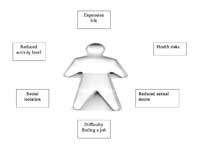

Since the students are now familiar with the concept of BMI and the definition of obesity, get them to discuss in small groups the problems of obesity and the necessity for help, with the aid of Worksheet 3w1.

Ask the students to imagine they were obese and answer the following questions:

The discussion should lead the students to the conclusion that obesity is a sign of disturbed homeostasis, when some individuals do not recognise satiety because their L cells may not function properly. Treatment with oxyntomodulin has the potential to cause weight loss by correcting the body’s energy balance, enabling a healthy weight to be maintained.

Before oxyntomodulin can be used widely to treat obesity, further study is necessary. From Wynne & Bloom (2007), use the box about clinical drug trials (below) to show that before drugs are licensed, they go through many stages of testing to identify and minimise side effects.

The following questions may arise or could be posed:

Ask the students to write a short essay – either a creative story or a factual discussion – about the possible impact of using oxyntomodulin to treat obesity.

Finally, the students could discuss whether this type of research should be funded at all. Why? Why not? With my students, this led to a lively debate, including the point that many more people starve to death around the world than die of obesity-related problems.

By the end of the unit, the students should have understood that our organ systems depend on and influence each other, and that if one parameter is changed there will be a chain of changes elsewhere in the system. This is true of any disturbance of body homeostasis, whether overeating, starvation or even drug abuse.

New drugs must go through a series of trials, known as phases, in order to test whether they are effective and safe.

PHASE I: Early trial in a small number of usually healthy volunteers to establish a safe dose and look for potential side-effects.

PHASE II: Larger group trial of volunteers (up to 100) with the illness to be treated, to establish short-term effectiveness and safety. Both studies described in this article were early Phase II trials.

PHASE III: Large group drug trial of volunteers (up to several thousand) with the illness, over an extended period of a year or more to compare the treatment with an existing therapy or a placebo.

PHASE IV: Drug trial usually performed after a treatment has been licensed, to establish the effectiveness of the treatment when it is used more widely and to investigate long-term risks and benefits.

This process is essential to ensure that the benefit of the treatment is greater than any possible side-effects, but it means that it can take several years for a new drug to reach the public.

| Phase | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | |

| Number | 124 | 259 | 169 | 55 |

If you have used one of our science articles in your lessons, please tell us how. Contact: editor@scienceinschool.org

When students are actively involved in their lessons, they always both enjoy and learn more. This article shows how this can be achieved using a cutting-edge science article from Science in School that can be used to cover a whole topic of the curriculum.

The work is involved and will challenge many students with mathematics, biology and discussions on health and well-being. The students must feel secure in the classroom before they begin to discuss weight issues and it may be a good idea to mention that personal issues are confidential and should not be discussed outside the room.

The issue of drugs to control weight and promote weight loss is an interesting topic and could be extended to include herbal and over-the-counter products. Students could discuss the social, commercial and ethical issues of weight-loss products and promotions. It should be a fun and interesting way of studying a topic by making it relevant to the students’ own lives.

Shelley Goodman, UK