A chromosome walk

Stroll through biological databases: Walking on chromosomes is a CusMiBio project that teaches students how to explore biological databases and…

A new short film explores the science behind gene therapies, with the help of five leading experts in the field and a unique, stop-motion animation.

Created by EuroGCT, Gene Horizons is an 18-minute documentary film which uses stop-motion animations to explain the science behind gene therapy. By combining engaging, scientifically accurate imagery with interviews from five leading experts in the field, the film offers an inside look at how this cutting-edge technology is already being used to treat genetic disease and other conditions.

Gene Horizons provides an overview of the fundamental science of gene therapy and outlines three examples of how it is currently being used. The film also creates an opportunity to discuss the benefits and risks of new medical technologies, encouraging critical thinking around the social and ethical impact of scientific discovery. A toolkit containing more in-depth resources on the topics covered in the film, including a quiz to use in the classroom, is available at www.eurogct.org/gene-horizons.

EuroGCT is a consortium of 47 partner organisations and institutions across Europe, with the goal of providing reliable and accessible information about the science of cell and gene therapies, and their societal and ethical impact. The project, and this film, was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme.

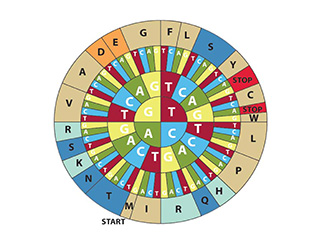

Genes are short sections of DNA. They contain the precisely coded information needed to build proteins, which are the building blocks of our bodies. Mistakes in the code, or ‘mutations’ in genes can lead to disease.[1] Gene therapy is being used to correct or replace these miscoded genes, by introducing a healthy copy of the affected gene or editing the faulty gene in a patient’s cells.[2] Gene therapy can be used to treat many types of diseases, including some types of cancer.

Viruses infect our bodies by using specialised proteins to inject their own genes into cells. In the 1970s, scientists discovered that this natural property of viruses could be used to add genes to human cells.[3,4] The harmful part of the virus DNA is removed, and the desired gene is added, turning the virus into a harmless delivery vehicle that simply carries the gene-therapy instructions into the body’s cells. This is called a viral vector and is one of the main methods used in gene therapy, although scientists are currently studying other ways to deliver genes into cells.

But what kind of diseases can currently be treated with gene therapies? Below are three examples covered in Gene Horizons.

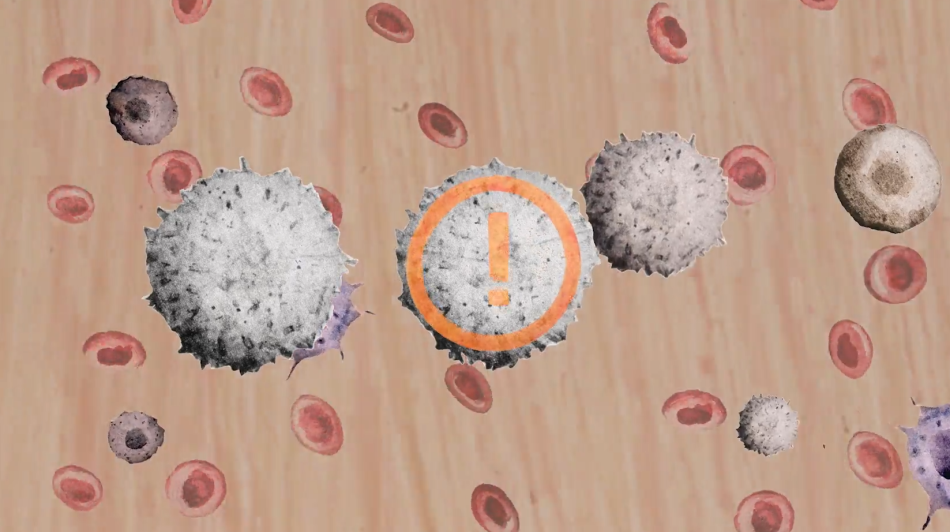

People with Severe Combined Immunodeficiency Disorder (SCID) can’t produce functional white blood cells, which are responsible for fighting infection. People with this condition are left with little to no immune system, putting them at high risk of life-threatening infections.[4,5]

SCID is caused by mutations in genes that make proteins required for the white blood cells to function properly. White blood cells are normally produced by blood stem cells, which live in the bone marrow and produce all the different cell types that make up our blood.

To treat SCID with gene therapy, doctors collect some of the patient’s blood stem cells and use a viral vector to introduce a correct copy of the faulty gene into the cells. Because blood stem cells make white blood cells in the immune system, the patient’s stem cells can now make healthy white blood cells. The corrected stem cells are reintroduced back into the patient’s body, where they can produce a working immune system. For SCID, correcting only 5–10% of the blood stem cells can have a huge impact.[5]

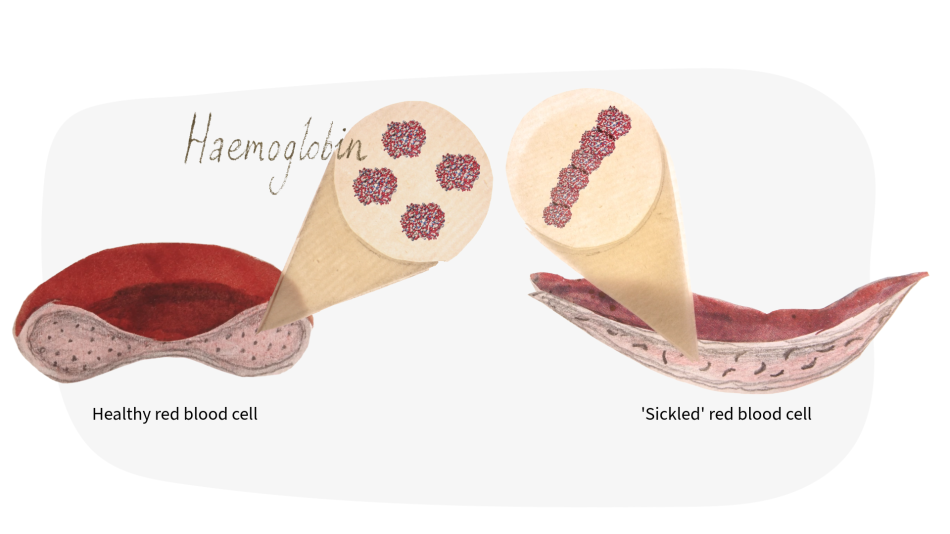

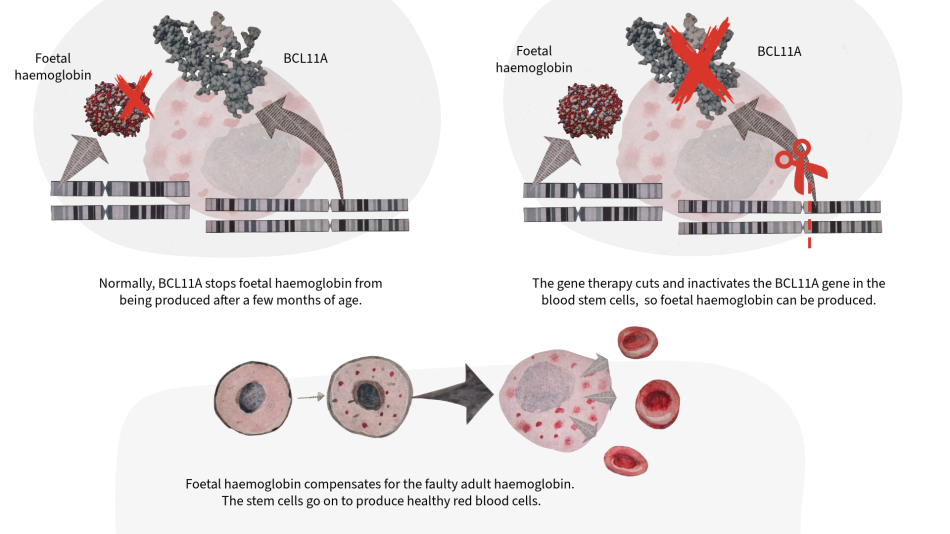

Sickle cell disease (SCD) affects red blood cells, which carry oxygen through the body. SCD is caused by a mutation in the haemoglobin A (adult) gene, which causes the protein it produces to clump together. This means the red blood cells become crescent or ‘sickle’ shaped, leading to blood vessel blockages that cause severe pain and organ damage.[6,7]

Humans have more than one type of haemoglobin. Foetal haemoglobin is only active during early stages of life and becomes dormant (inactive) when adult haemoglobin takes over. However, in people with SCD, the adult haemoglobin gene is faulty. To treat SCD with gene therapy, doctors target the BCL11A gene, which is responsible for switching off foetal haemoglobin. A technology called CRISPR-Cas9 is used to directly target and cut the BCL11A gene in patients’ blood stem cells, deactivating it. This means foetal haemoglobin is no longer suppressed and can compensate for the faulty adult haemoglobin.[6] Since blood stem cells also make our red blood cells, this treatment allows healthy red blood cells to be produced.

A new kind of gene therapy, known as CAR T cell therapy, is being used to treat certain blood cancers. T cells are a type of white blood cell that normally detect cancerous cells using specialised receptor proteins on their surface, but sometimes they fail to recognise them. In CAR T cell therapy, the receptor proteins on the surface of T cells are genetically modified, allowing them to recognise, attack and kill specific cancer cells.[8] The difference between CAR T and other gene therapies is that it doesn’t try to address the underlying cause of the disease. Instead, it changes the healthy cells to make them better at identifying and killing cancer cells.[9]

In this therapy, T cells are taken from the patient’s blood, and a gene for a specially modified receptor is added. The T cells are returned to the body, where they can attack the cancer. This treatment is currently only used for some types of blood cancer, but researchers hope that one day it can be used to treat other kinds of cancer, including solid tumours.[10]

Gene therapy comes with both promising benefits and important risks , which must be balanced for each patient individually. Currently, it is only used to treat a small number of conditions. A major challenge lies in delivering the right dosage of therapies into the right cells and organs within the body. For this reason, disorders affecting the blood have been the frontrunners in gene therapy development, as blood can be taken from the body and safely worked on in the lab. Ongoing research is focused on finding better ways to deliver genes into cells, and to target specific cell types more accurately.

Scientists have high hopes that gene therapy will one day be used to treat many genetic conditions that currently have no cure, as well as other conditions like different types of cancers and even autoimmune diseases like lupus and multiple sclerosis.[10,11]

[1] Interactive informational source on genes and DNA: https://www.abpischools.org.uk/topics/genes-and-inheritance/genes-and-dna/

[2] Explanation of gene and cell therapy: https://www.eurogct.org/what-gene-and-cell-therapy

[3] Video explanation on viral vectors: https://patienteducation.asgct.org/understanding-cell-gene-therapy/viral-vectors

[4] From the interview with Professor Claire Booth in Gene Horizons:https://www.eurogct.org/gene-horizons

[5] Information on Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID): https://www.gosh.nhs.uk/conditions-and-treatments/conditions-we-treat/severe-combined-immunodeficiency-scid/

[6] Information on Sickle Cell Disease: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/sickle-cell-disease/

[7] From the interview with Dr Subarna Chakravorty in Gene Horizons:https://www.eurogct.org/gene-horizons

[8] Information on CAR T-cell therapy: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/treatment/targeted-cancer-drugs-immunotherapy/CAR-T-cell-therapy

[9] From the interview with Professor Julio Delgado in Gene Horizons:https://www.eurogct.org/gene-horizons

[10] News report talking about Car-T Cell therapy applied on a young MS patient: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/ms-multiple-sclerosis-symptoms-car-t-cell-treatment-nhs-b2852047.html

[11] Fieldhouse R (2025)‘They don’t have symptoms’: CAR-T therapies send autoimmune diseases into remission. Nature 648: 16–17. doi: 10.1038/d41586-025-03885-w

Stroll through biological databases: Walking on chromosomes is a CusMiBio project that teaches students how to explore biological databases and…

A controversial new technology is making gene editing far cheaper and easier – too easy,…

How does cancer develop, and how can geneticists tell that a cell is cancerous? This teaching activity developed by the Communication and Public…