Plastic food packaging: simply awful, or is it more complicated? Understand article

Why is food sold in packaging? Do we really need it? And if so, what materials are best? These questions are more complex than they seem and the answers may surprise you.

The food we buy is usually packaged in some way. However, the packaging ends up as waste and often causes problems in the environment. Waste is always bad: did we need the packaging at all? And if we must have packaging, what materials should we use? These are difficult questions and the answers aren’t so obvious.

Why use packaging?

Some things are obvious: we need to be able to handle liquids and powders, so they have to be in containers. Furthermore, labels on packaging provide information about the contents and sealed packaging provides quality assurance. But perhaps the most important function of food packaging is to protect fragile or perishable foods from damage or deterioration, keeping them fresh longer and reducing food waste.

| Traditional packaging | Recommended plastic packaging | Shelf life difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

Bananas | Sold loose | Polyethylene film bag | 5 days unpackaged; extended to 36 days in bag |

Beef steak | (a) Wrapped in paper (b) rigid tray with cling film wrap | Vacuum packed in oxygen barrier film | (a) 2 days in paper; (b) 4 days in cling film. Extended up to 30 days in oxygen barrier film |

Bread | Paper bag | Polypropylene film bag | Typically 1 day in paper bag; extended to 5 days in plastic bag |

Cheese | Wrapped in paper | Multilayer barrier film bag | 3 days in paper bag; extended to up to 280 days in barrier film |

Cucumber | Sold loose | Polyethylene shrink wrap film | 3 days unpackaged; extended to 14 days in shrink wrap |

Images: Bananas: date-limite-app/ Open Food Facts, CC BY-SA 3.0. Steak: Mj/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0. Bread: FranHogan/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0. Cheese: garyzing1221/Pixabay. Cucumber: Markus Winkler/Unsplash

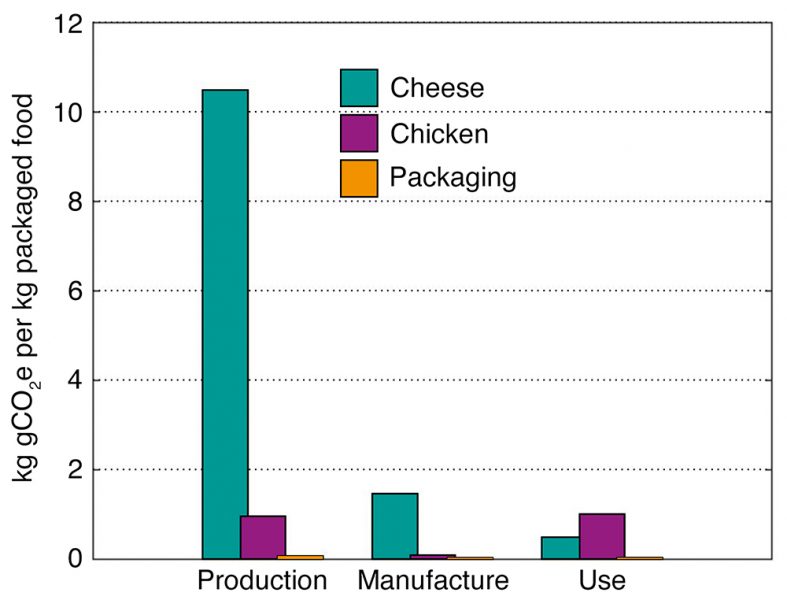

The role of packaging in increasing shelf life and thus reducing food waste is important because a large part of the carbon footprint from our diets arises from the foods themselves, with packaging adding only a tiny amount. Food waste is a huge environmental problem.[1]

Image courtesy of the author

Looking at the relative carbon footprints of the cheese and the packaging, we find the packaging footprint is less than 1% of that of the cheese, so this packaging can save a lot of carbon.

Although there are benefits from packaging food, it also has downsides. It consumes energy (often from burning fossil fuels, which releases CO2) and resources (e.g., water) to produce, and disposal after it has fulfilled its purpose can be a problem, particularly for plastic. So what is the best material?

Plastic – pros and cons

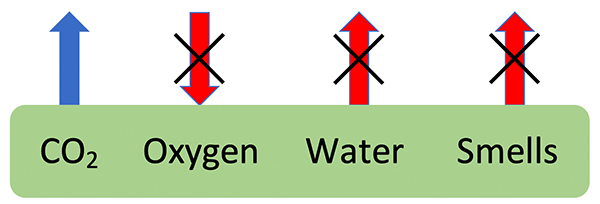

Often, packaging must fulfil several complex functions. Take the example of cheese films.

Case study: Cheese packaging

What does the packaging need to do?

- It should provide mechanical protection (must be strong and tough).

- It must act as a barrier to certain gases:

- Cheese matures in the package, releasing CO2, which needs to escape.

- Without packaging, cheese loses 10% of its water in three days, so the film needs to be impermeable to water.

- The cheese should be protected from oxygen and we need to keep smells in (a range of gaseous organic molecules).

How can a single film achieve all these different functions?

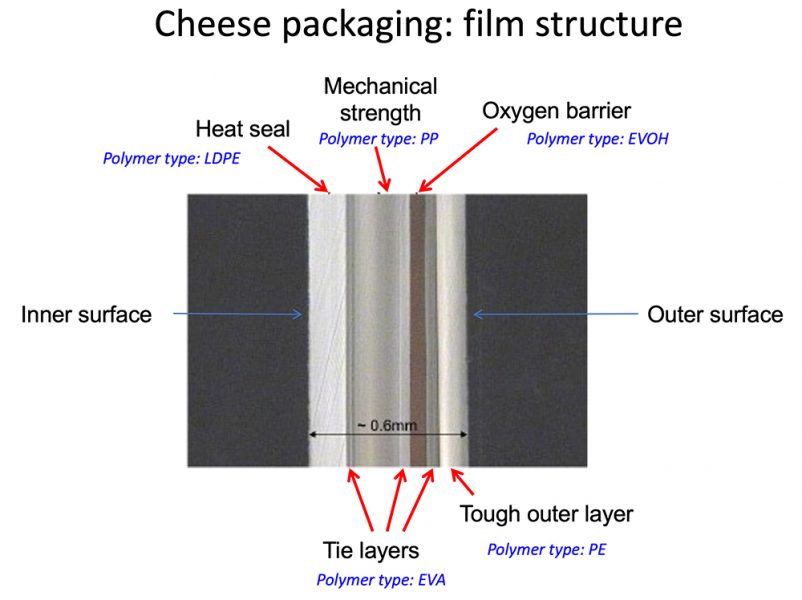

This microscopy picture reveals the seven different polymer layers in this cheese film, made by co-extrusion.

| LDPE | Low Density Polyethylene | Softens on heating: inner surfaces of two films heated and pressed together to seal package |

| PE | Polyethylene | Low friction and high toughness to resist scuffing damage on surfaces |

| PP | Polypropylene | High strength and toughness to resist damage by tearing |

| EVOH | Ethylene Vinyl Alcohol Copolymer | Low permeability to oxygen: oxygen barrier |

| EVA | Ethylene Vinyl Acetate | Adhesive: thin coating used to bond different poylmer layers together |

Plastics have many beneficial properties for food packaging. They can be manufactured to serve different purposes and thin films can be used to minimize the carbon footprint of the packaging. Plastics are also very good at controlling gas and moisture flow. But what are the downsides?

The main downside of standard plastic is what happens to it after use. It doesn’t biodegrade so it will persist in the environment for a very long time. There is limited space for landfill disposal and often plastic ends up in the environment where it can harm wildlife, especially in the oceans.

What about recycling?

Plastics can be melted down and turned into other plastic objects. This reduces landfill and litter and decreases the amount of new polymer that needs to be made through energy-intensive processes (oil refining, cracking, polymerization). This can save about one tonne CO2 per ton of polymer.

Material (mechanical) recycling of polymers

The main polymer recycling process for post-consumer waste is mechanical recycling.

Image courtesy of the author

The steps are:

- Sorting

- Cleaning

- Shredding

- Melting

- Cutting into pellets

Image courtesy of the author

These pellets of recycled plastic are then usually mixed with virgin (new) plastic and used to make further products.

However, in practice, there are many challenges.

The first is that for good-quality recycled plastic, a fairly clean type of used plastic is required. This not only means that the item should be free of food residue but also ideally a single type of plastic without too many additives, including colourants.

As we’ve seen from the cheese film example, many plastic-based packaging materials contain multiple layers of different plastics or even plastic mixed with other materials (e.g., Tetra Pak), and these are very difficult to recycle. A single polymer is easier to recycle than a multilayer film, but may have to be thicker to provide the same barrier properties. The best single substitute material is polyethylene terephthalate (PET), but it has to be 20 times thicker, which results in 20 times the carbon footprint.

Another challenge is that most recycling involves ‘downcycling’, that is, the recycled plastic can only be used for lower-grade applications (e.g., fleece jackets from PET bottles), and so doesn’t save resources in the same way.

Alternative materials

While other materials may be less harmful to wildlife, it is important to take the environmental costs of manufacturing them into account.

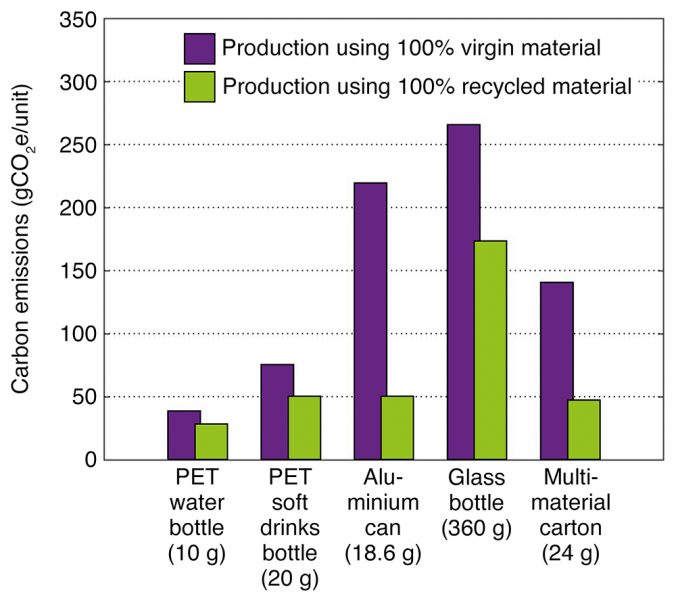

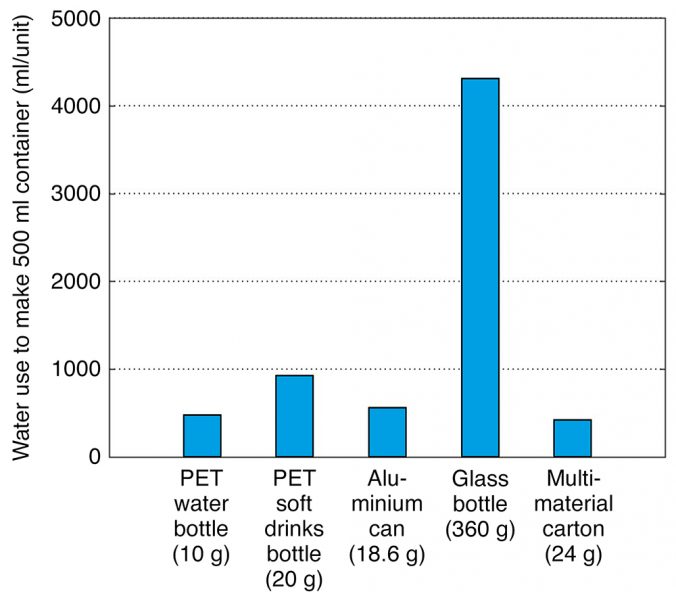

Let’s compare different materials for a 500 ml beverage container.[3] We need to consider primary factors, like the manufacturing environmental impact (carbon, water), and secondary factors, like transport. Glass containers are heavy and bulky so the energy for transportation is much higher.

Image courtesy of the author

Containers made from plastics have the lowest carbon footprint, although recycled aluminium can be nearly as good. Glass, even recycled glass, has a much higher carbon footprint than plastic. A good low-carbon option is to return glass bottles and jars so that they can be cleaned and used again, rather than being broken up and melted to make new glass objects.

Image courtesy of the author

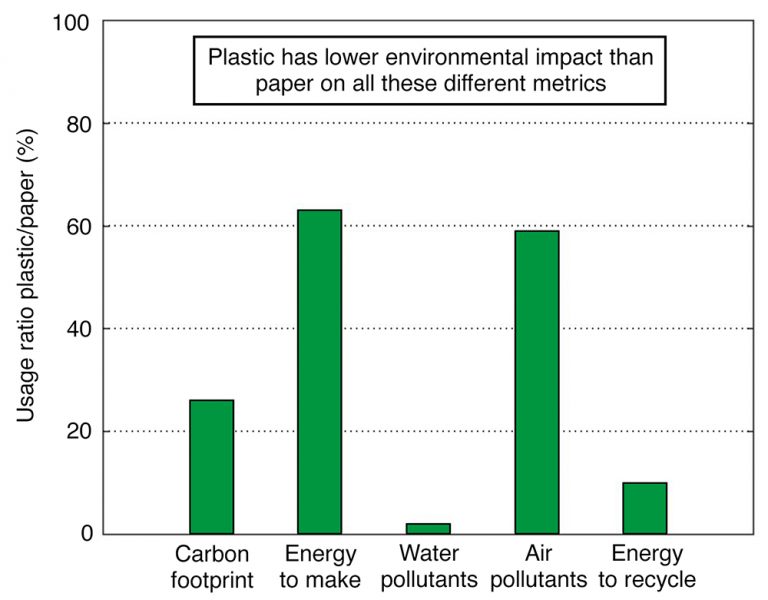

Thus, although public pressure is to go ‘plastic free’, the question of whether this is really better for the environment is not straightforward. This becomes particularly clear when comparing the environmental impact of different types of shopping bag.

Biodegradable materials

Cardboard and paper degrade naturally, so they avoid the litter problem. However, they can have a greater environmental impact than plastic in other ways. The carbon footprint is high because the manufacturing operations for paper and cardboard are very energy-intensive (chipping and processing trees requires 60% more energy than making plastics). Papermaking also generates much more toxic waste than plastics (water pollutants 50 times higher; air pollutants 70% higher).

Image courtesy of the author

Paper and card that is clean can be recycled after use, although this requires about ten times more energy than recycling plastics. However, after use as food packaging it is often soiled and must be treated in the same way as waste food (ideally composting or anaerobic digestion).

Other bio-based biodegradable materials are being developed as substitutes for petrochemical-based plastics and there’s some very promising activity, particularly in small-scale initiatives using waste materials such as sugar-cane or maize stalks.

Conclusions

Food packaging can be important because it has a part to play in reducing food waste, which has a big environmental impact. Plastic has some major downsides, but just directly replacing it with other materials might not always be better for the environment.

Packaging is not all bad but we do need to reduce its environmental impact by:

- using less packaging and eliminating unnecessary packaging (e.g. single-use water bottles)

- using materials that can be better recycled and increasing recycling

- reducing single-use packaging in favour of re-usable packaging (not just for plastic)

- looking for alternative packaging materials and methods that really are more environmentally friendly, making sure to assess and include all lifecycle impacts

Remember that a really powerful way of reducing waste, of both food and packaging, is to buy only as much as we need!

Actions to protect the environment should be based on data, not a gut feeling that certain approaches, such as using less-modern materials, are automatically better. The real situation is complex and the results can be surprising.

References

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2015) Food waste footprint & climate change.

[2] Barlow CY, Morgan DC (2013) Polymer film packaging for food: An environmental assessment. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 78: 74-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.07.003

[3] University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL) (2020). Towards sustainable packaging materials: Examining the relative impact of materials in the natural source water and soft drinks value chain.

Resources

- Explore some European food waste statistics from The European Food Information Council (EUFIC)

- Take a look at this infographic on food waste in the EU. How does your country rate?

- Watch a video on the problem of food waste from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Learn how you can reduce food waste and become a food hero.

- Read about some of the supermarket practices that affect food waste.

- Watch a video on some of the factors that contribute to food waste.

- Read an article about the glass environmental footprint on BBC Future.

- Watch this engaging video on the relative environmental impact of different types of shopping bags. The conclusions might surprise you!

- Read about the impact of human activity on climate change and its consequences for the Earth: Follows M (2019) Ten things that affect our climate. Science in School 47: 19–25.

- Explore the water footprints of the foods we eat: Kelly S (2020) Do you know your water footprint? Science in School 50.

Review

A note from the editor:

The topic of sustainability with respect to consumer items and especially food is a vast and complex one, as well as being extremely important. Unfortunately, it was only possible to touch on one small aspect in this article: that of packaging materials. And even then, there wasn’t space to go into some of the newer technologies in this space, such as edible biodegradable coatings. Hopefully, we will have an article on this in the future. Another key point is the importance of proper disposal of all waste, not just plastic. Landfill does not provide good conditions for biodegradation, so if biodegradable packaging is thrown into the normal waste, it will still persist in the landfill for a very long time.

This article can be used as a starting point for a wider discussion of this topic. In particular, the environmental cost of food waste is often neglected and deserves more attention. How perishable foods are packaged is, of course, only one small factor. There are some resources provided at the end of the article to help introduce this topic, and the following points could be discussed:

- Imagine the fruit and veg section of a supermarket. Do you often see produce running low or older produce displayed, or are the displays usually piled high with perfect new produce? Do you think all this produce is purchased before it goes bad? Why do supermarkets do this? (Hint: look up “Illusion of abundance”). What could be done to solve this?

- Approximately what percentage of food waste is due to consumers throwing food away? What are the behaviours that contribute to this and what can individuals do to minimize their contribution to food waste?

- What are the factors that contribute to food waste? Consider all stages of the process: production, distribution, retail, and consumption.

- What steps could be taken to reduce waste at these different stages?

- Do some of those steps rely on individuals changing their behaviour? How can this be encouraged?

- What role can legislation play? What about consumer pressure?

- Ask students to go to the supermarket and pick some products with “green” claims on the packaging. Discuss whether these claims are really meaningful or just a cynical marketing gimmick.

As this article shows, the evidence doesn’t always match people’s gut feelings, and the best option isn’t always easy to identify. People can land up focusing so much on just one very visible factor (e.g., plastic litter) that other equally important factors (carbon footprint, water footprint) are overlooked. We need to guard against being misled by wishful thinking or conveniently oversimplified explanations and ensure that we take meaningful, evidence-based action to help the environment.

Dr Tamaryin Godinho, Executive Editor, Science in School