Supporting materials

Instructions for preparing cyprinum and rhodinon Table 1 (Word document)

Instructions for preparing cyprinum and rhodinon (PDF file)

Download

Download this article as a PDF

Even everyday scents have the power to take us back in time, awakening half-forgotten memories. With Gianluca Farusi’s help, you can take your students 2000 years into the past, recreating and testing Julius Caesar’s perfume.

Dictator of the Roman Republic until 44 BC, he invaded Britain and was the first Roman general to cross the River Rhine. He was the lover of Queen Cleopatra, and the month of July is named after him. Julius Caesar is famous for many things – but probably not for his choice of perfume.

Perfumes, however, were an important part of life in ancient Rome: in the form of incense for religious ceremonies; in public areas to mask foul smells – Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) records rose-scented water being sprinkled in theatres; and for moisturising the skin.

Today, most commercial perfumes are alcohol-based, but Roman perfumes for the skin took the form of unguents, or greasy ointments. An unguent consisted of a liquid base and a scented essence, and could also contain preservatives such as salt, and fixatives such as gums or resins – to stabilise the volatile components of the perfume.

One of the most frequent liquid bases used was omphacium, an oil extracted from green olives or unripe grapes. To obtain scented essences, the Romans used many methods to extract scent from flowers, seeds, leaves, bark and other fragrant plant material. Many of these methods are still used today.

How do we know so much about Roman perfumery? Partly, of course, from contemporary written records – but science can also help. Modern archaeological analyses of perfume traces in ancient pots can help to identify the perfume, the way it was prepared and even what it was used for. By combining chemical data with information from contemporary authors, we can reproduce some of the perfumes of the ancient world.

“…Ratio faciendi duplex, sucus et corpus: ille olei generibus fere constat, hoc odorum.… E vilissimis quidem hodieque est – ob id creditum et id e vetustissimis esse – quod constat oleo myrteo, calamo, cupresso, cypro, lentisco, mali granati cortice.… Telinum fit ex oleo recenti, cypiro, calamo, meliloto, faeno Graeco, melle, maro, amaraco. hoc multo erat celeberrimum Menandri poetae comici aetate.

Unguents comprise two elements: the juices and the solid parts. The former generally consist of various kinds of oils, the latter of odoriferous substances.… Among the most common unguents today, and for that reason assumed to be the most ancient, is that composed of oil of myrtle, calamus, cypress, cyprus, mastich, and pomegranate rind.… Telinum is made of fresh olive oil, cyperus, calamus, yellow melilot, fenugreek, honey, marum, and sweet marjoram. It was the most fashionable perfume in the time of the comic poet Menander [around 300 BC].

Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia (Natural History), book XIII, chapter 7, paragraph 9

As part of a larger interdisciplinary chemistry project (see box), my students (aged 14-15) and I decided to do just this: recreate the favourite perfume of Julius Caesar. But how did we even know what it was? Thanks to a fragment of poetry attributed to Caesar (‘Corpusque suavi telino unguimus’, ‘We anoint the body with fragrant telinine ointment’), it is thought to be the unguent telinum.

However, finding the recipe is no easy task. For one thing, before the introduction of Linnaean taxonomy, there was no consistent naming convention. Thus, for example, the name ‘cyperus’ may refer to the many species of sedge (Cyperus spp), to gladioli (Gladiolus spp), to lemongrass (Cymbopogon schoenanthus)or even to privet (Ligustrum spp). Moreover, perfume recipes – then as now – were fiercely guarded by their manufacturers, so even though contemporary writers sometimes recorded the ingredients of a perfume, they seldom mentioned the proportions.

In the case of telinum, we were lucky: in his Naturalis Historia (Natural History), Pliny the Elder records the ingredients (above) and Pedanius Dioscorides (c. 40-90 AD) records somewhat different ingredients but does mention the proportions in his De Materia Medica (On Medical Materials).

For our recreation of telinum, therefore, we carried out a series of trials based on these two ancient recipes, to determine the blend we preferred. How should we interpret ‘cyperus’, though? We prepared two versions: one with lemongrass oil and one with violet oil (Viola odorata) – because the roots of both gladioli and Cyperus species smell like violets.

Finally, because marum (Teucrium marum) is thought to be carcinogenic, we decided to replace it with catmint (Nepeta cataria), which smells similar. If not entirely historically accurate, our perfume should at least smell like Caesar’s.

It is not clear from the historical sources whether dried or fresh materials were used. We used dried materials, as they contain more scent per gram and are easily obtainable: try a chemist or herbalist’s shop.

To prepare omphacium for our project, I picked the green olives, ground them in the kitchen mixer, collected the mixture in a tea towel and squeezed the oil into a bowl. I then filtered the oil three times using filter paper, and centrifuged it twice for 5 min each time.

Alternatively, use shop-bought olive oil.

I divided the class into three groups; each group prepared a different historical perfume (instructions for preparing cyprinum and rhodinon can be downloaded from the Science in School websitew2). At the end of the activity, each student had a small sample of perfume to take home.

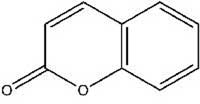

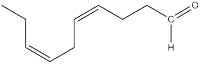

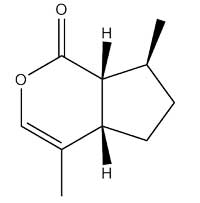

Once we had appreciated the perfume of ancient Rome, we returned to the 21st century to investigate which molecules produced the fragrance. Table 1, showing the main scented chemicals in our telinum (the structures of some of which illustrate this article), is available for download from the Science in School websitew2.

With older students, this activity could be used to investigate organic chemistry in some detail. With my 14- to 15-year-old students, I concentrated on the basics of the chemistry of smell. For example, I asked them:

Check your national or local safety guidelines to see if you are allowed to use lab-prepared materials on the skin.

By the end of the activity, together with some associated experiments, the students had established that:

This activity is part of a larger interdisciplinary project, developed together with my 14- to 15-year old students, to meet the curriculum requirements at that age. We began each session (1-4 two-hour lessons) by discussing a passage from Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia, then worked out how to recreate in the laboratory either the event described in the text or something similar. In this way, the students began in the same pre-scientific state as Pliny and, through laboratory work and discussion, gained modern scientific knowledge on each of the topics. The process motivated even the most unenthusiastic students.

Other activities in the project include extracting indigo from woad, preparing glass tesserae with boric acid, simulating the luminescence of the shellfish Pholas dactylus, and preparing iron-gall ink (Farusi, 2007).

The author would like to thank Graziella Zacchini of the Officina Profumo Farmaceutica Santa Maria Novella, who provided plant materials used in the project.

This article provides an opportunity to link history with practical chemistry. Learners will be swept away into Roman times, to learn why our ancestors extracted scents from plant material and turned them in a form that could be applied onto the skin. It is highly beneficial for students to connect their current scientific knowledge to its roots. Following the path of our scientific forefathers helps us to understand the development of the scientific process as well as how organic substances have been developed into useful materials.

The activity could be used in biology (plant histology; physiology of smell), chemistry (organic chemistry; molecular chemistry) and history (the Romans; the history of chemistry) lessons. It could also be used as the basis for a discussion on the use of natural as opposed to man-made substances in beauty products. How sustainable is the use of natural products for large-scale production?

Information is provided in the article about different methods of extracting scents. As an extension of the project, the students could investigate these methods further – both on the Internet and in the laboratory. Teachers could also extend the activity and bring the scents closer to home by using local plant material to create perfumes: reliving their country’s past through plant life. Local universities are usually an excellent source of information on native species. When collecting plant material, attention should be paid to local safety measures, and endangered species should be avoided.

Angela Charles, Malta