Teaching science and humanities: an interdisciplinary approach Teach article

There is an increasing demand for an interdisciplinary approach to teaching, but providing inspiring and achievable lessons is no easy task. Chemistry teacher Gianluca Farusi explains how he used two Italian Renaissance paintings to delve into the chemistry of pigment extraction and the physics of…

An interdisciplinary approach

1472-74 (tempera on panel)

by Piero della Francesca

(c.1419/21-92).

Courtesy of the Pinacoteca di

Brera, Milan, Italy / Alinari /

The Bridgeman Art Library

Students are often unaware of the links between the sciences and humanities, as a result of the differences – and, sometimes, opposition – in the way the subjects are taught. In an interdisciplinary approach, a painting provides a very useful starting point. We considered Piero della Francesca’s Pala di San Bernardino from different points of view.

Approaching the painting from the perspective of the humanities, we asked students to consider its abundant symbolism. For instance, the infant Jesus wears a necklace of coral beads with a small coral branch lying on His chest. Is it a chance choice? Certainly not! The red of the coral represents the blood of Christ (placed on the chest, where Jesus was speared on the Cross), and is symbolic of the Passion and the Resurrection. The ancient Greeks, in fact, connected coral with a heroic feat of Perseus: when he cut off Medusa’s head, the gushing blood changed into coral upon contact with the sea, and for this reason, coral is a symbol of rebirth. Students could also discuss the symbolism of the shell, the ostrich egg or other features of the painting.

In terms of mathematics, perspective and the golden ratio are undoubtedly the most important topics to address, but students could also set themselves a geometric goal: to calculate the volume and the area of the vault, for example.

Students addressed the earth sciences by identifying the stone illustrated on the walls, by comparing it to samples of marble, jasper, porphyry and other materials on display in their local museum. Other possibilities in the earth and natural sciences would be to investigate the gems worn by some characters, or to identify the clams and coral and to study their natural environment and life cycle. The most appropriate discussions would depend on the type of museum available.

The chemist’s imagination is bound to be captured by colours, and so we decided to prepare one of the pigments that was used by the painter. What kind of pigments did he use? When a painter or a painting is as famous as Piero della Francesca and his works, you can find a lot of information on the worldwide web. Further assistance was available from the Monuments and Fine Arts Office for Pisa, Lucca and Massa Carrara. We looked through entries and reports, and discovered that the linen cloth on the nine wooden boards which support the painting was dyed with alizarin lake. Alizarin is obtained from the roots of madder, Rubia tinctorum, a common European plant. And so we departed for the woods and hills, looking for madder roots…

From madder to alizarin

Alizarin is one of two main dyes, the other being purpurin, that come from the roots of the madder plant. It was used to dye cloth in Asia in ancient times and in Egyptian textiles as early as 1600 BC. Its first known use on paper is much later, in 972 AD, when it was used as ink on the marriage certificate of the Byzantine Empress Theophano. It has been used in painting since the 16th century.

Madder, common across Europe, is a crawling plant up to 1.5 metres long. The flower is white-yellow and the fruit is a pink-red berry. The stem bears clusters of five or six leaves, the lower sides of which are sticky and rough. The roots are reddish.

Alizarin exists mainly in the fleshy roots in the form of its glycoside, ruberythric acid. Pieces of rinsed roots are treated with a hydrochloric acid solution to hydrolyse the ruberythric acid and remove flavonoids, which would otherwise dull the pigment. The roots are then dried and treated with a solution of alum to extract the alizarin, which forms a red complex.

To obtain the pigment, a soda solution is added to precipitate aluminium hydroxide, which adsorbs alizarin. The pigment, once strained, rinsed and dried, can be used for tempera and oil painting.

Alizarin extraction

The alizarin content of the roots depends on the season and on the kind of soil, although the average content is about 1.9% w/w.

- Soak x g of dried madder root in 0.27 M hydrochloric acid solution (HCl) for 48 h at room temperature. Remove the roots and dry them.

- Add 1.9x cm3 of alum solution (KAl(SO4)2.12H2O) at a concentration of 0.021 mol/l. Al3+(aq) + 2C14O4H8(aq) → Al(C14O4H8)23+(aq)

- Boil the mixture for 3 h, keeping the volume constant by adding small quantities of water.

- Allow the mixture to cool and separate the roots from each other.

- Dropwise, add 0.63x cm3 of soda (Na2CO3(aq)) at a concentration of 0.094 mol/dm-3 to the solution. 2Al(C14O4H8)23+(aq) + 3Na2CO3(aq) + 3H2O(l) → 2Al(OH)3(s) + 4C14O4H8(s) + 3CO2(g) + 6Na+(aq)

- Once the pigment has precipitated, collect it using a Buchner funnel, and rinse and dry it.

The search for hidden images in paintings

From the physicist’s perspective, a painting is an excellent opportunity to investigate the interaction between matter and electromagnetic waves. The multispectral imaging technique fitted the bill, but where could I find the necessary equipment? And how to do the study? A multispectral imaging investigation of a painting as famous as one of Piero della Francesca’s would be too much to hope for!

I contacted the Pisan branch of the National Research Council and Vincenzo Palleschi, head of the Applied Laser Spectroscopy Laboratory, was enthusiastic. A fellow teacher of mine, Lucilla Simonini, a literature teacher, suggested we study Pietro da Talada’s works. This minor 15th-century painter can be tentatively identified with the Maestro di Borsigliana and was an exponent of the International Gothic style. Most of his paintings are kept in churches in Garfagnana, northern Tuscany, but two are in Lucca at the Villa Guinigi Museum and at the Lucca Savings Bank Foundation. I contacted Mrs Filieri, head of the Monuments and Fine Arts Office, who allowed us to take photos of both paintings.

earlier painting

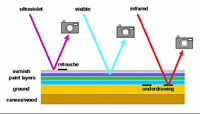

Multispectral imaging requires a digital camera interfaced with a monochromator and linked to a computer. The system records light intensity as a function of both wavelength and location. Images can be captured and analysed in broad spectral bands within the ultraviolet-visible and near-infrared regions, and processed and analysed with specially developed software.

If an image is captured in the red, green and blue bands, the superimposition of these three images results in an image of three times better quality than that of a normally exposed film. The image resolution depends on the pixel density on the sensor and on the pixel colour depth (pixel bits linked to each colour tone). With a 14-bit colour depth, we had 16 384 tones for each primary colour and (16 384)3 – almost 4400 billion – colours.

If a painting is illuminated by white light, blue-ultraviolet images include information mainly on surface features, whereas images captured at longer wavelengths carry information on deeper layers of the painting. Therefore, by taking images using different wavelengths, we hoped to discover pentimentos: hidden traces of earlier painting.

The chemical composition of a painting begins to change the moment the painter finishes working on it, because substances undergo oxidative and degradative processes, so pigment colours may change or fade with time. Further changes in composition may be due to restorations. When a mercury lamp filtered to transmit 365 nanometres is used as the excitation light source, part of the ultraviolet radiation is absorbed and given off with a lower energy in the visible region of the spectrum: as fluorescence. With this apparatus, we were able to look for restorations made with pigments that differed from those originally used by Pietro da Talada.

I have seldom seen my students working with such enthusiasm as when, burning with curiosity, they searched for pentimentos. One fine day, the much-anticipated discovery was made! While analysing the painting kept at the Lucca Savings Bank Foundation, we found a pentimento: Pietro da Talada appeared to have changed his mind about the position of a fold of cloth (see above). We were in seventh heaven!

The same day, using fluorescence, we discovered a restoration, highlighted by different shades of pink (see above).

It was a very snowy and cold day, but when I realized that my students were fully aware of how much beauty there is in science, and how much science in beauty, it warmed my heart.

Review

This article is an interesting indication of the links between the humanities and the sciences, showing different ways of approaching the topics of electromagnetic waves and dyes.

The protocol for extracting dye is straightforward enough to be carried out in schools and also provides a link to history and botany – as well as an excuse to take a chemistry class outside to search for plants.

The physics-based section describes an interesting way to introduce the idea of the electromagnetic spectrum but is probably more difficult to reproduce in most secondary schools, as it requires specialist equipment. It does, however, provide an interesting link to forensic science and how art forgeries can be identified.

The main difficulty with reproducing the science in this article in many schools would be in obtaining access to the specialist lighting and spectral analysis equipment as well as specific works of art. The article can, however, be used as a source of information or as a topic of discussion.

Mark Robertson, UK