Supporting materials

Download

Download this article as a PDF

Amazing Hydra: A spineless creature with astounding regenerative properties that can adapt to changing environments.

This module describes an activity on Hydra behaviour that is designed to teach students the scientific method via hands-on experiments and the value of quantitative measurements in biology. Hydra provides a simple model for students to understand organismal interactions with the environment.

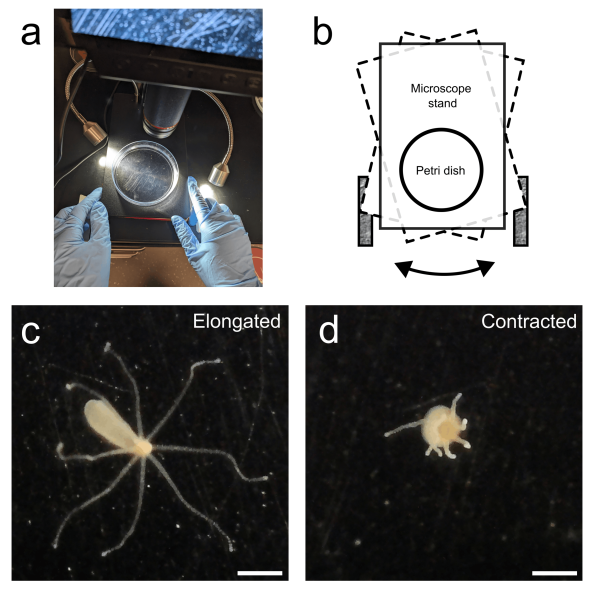

Students will measure changes in Hydra’s body shape in response to mechanical stimuli. The activity thereby explores how structure relates to function, a core concept from introductory biology, as well as how the nervous system senses external stimuli and triggers a behavioural response. This is achieved through hands-on experiments using a low-cost microscope and quantitative analysis.

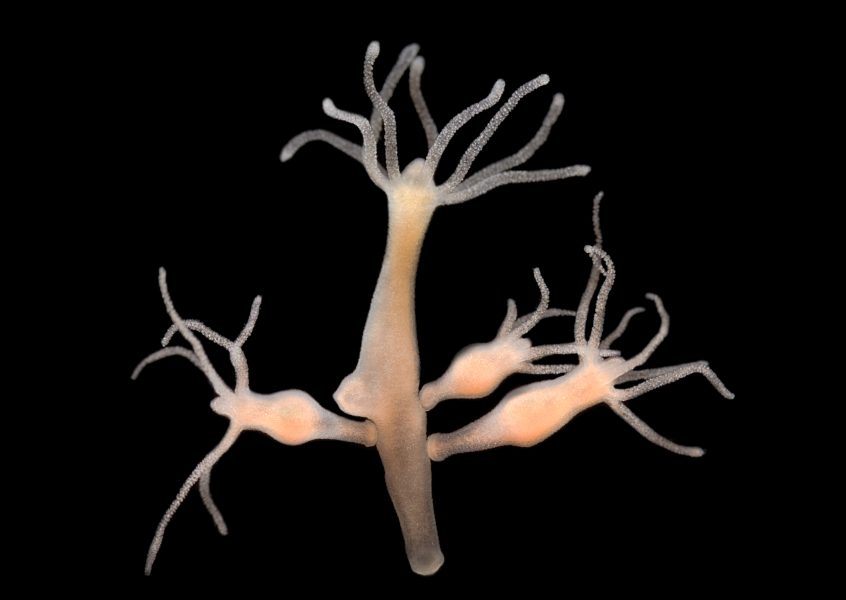

The experiments are easy to implement and modular, so they can be fitted into various time constraints. Hydra can either be obtained from local streams[1], from a Hydra research lab or obtained commercially (table 1). Hydra can be maintained in bottled spring water, and the cost and complexity of their care and handling is low, as described in this protocol.[2] The activity is aimed at students aged 11–19 years. Instructions for implementation, as well as worksheets and ideas to include independent inquiry and discussions about the ethics of animal research, are also provided.

Hydra contract in response to sudden changes in water movement or current, possibly as an escape mechanism and/or to prevent detachment from the substrate. After prolonged exposure to a new water current intensity, Hydra habituates, ceases contraction and elongates to its resting state.[6] This habituation behaviour reflects Hydra’s adaptability to changes in its environment. Students create water movement at two different frequencies (every 5 s and every 30 s for 2.5 minutes) through mechanical movement (moving the stage of the microscope) and record when and how often Hydra contracts. They take notes on their observations in worksheets and analyse and interpret their data.

The activity will take approximately 60 minutes.

Moving the microscope stage poses the risk of spilling water and Hydra, thus electronics should be positioned in a safe distance. With the exception of locally collected Hydra, Hydra should not be released into the environment after completion of the activities but discarded according to the protocol.[2]

While no animal welfare laws govern the use of invertebrates like Hydra in scientific experiments, it is still important to introduce ethical concerns of working with live organisms to student researchers. In this activity, the Hydra are mildly startled by the simulated river currents with no physical harm inflicted on the animals. For more involved experiments, additional considerations are required: these ideas will be explored in the “Discussion” section.

The activity can be performed without the microscope. Hydra are visible to the naked eye, so students can observe the animals by eye against a dark background, such as a piece of construction paper. A magnifying glass would be helpful to enlarge it.

Answers are provided in the answer sheet 1.

The introduction section of the article ‘Aquatic and terrestrial invertebrate welfare’ may be useful reading for students prior to a discussion.[7]

Project the class data (if available) and discuss the questions below using activity worksheet 2. Sample responses can be found in the answer sheet 2 in the supporting material.

The last section of worksheet 1 contains a fill-in-the-blank table with steps from the scientific method that could be completed in class or given as a homework assignment. Revisiting the scientific method info sheet, students are encouraged to reflect on how their experimental process fits with the scientific method.

Like Hydra, many other invertebrates inhabit the beds of natural freshwater sources and respond to varying conditions in their environment. The teacher can collect water samples with students from a local creek or pond and then use a microscope to study the behaviour and count the invertebrates living in the water. The abundance or absence of invertebrates can be used to assess water quality. References 8 and 9 can guide such an extension activity.[8,9]

The authors thank Vivien Zheng, Magnus Collins, and Nikita Collins for feedback on the activity and worksheet and testing the experiments. This work was partially funded by National Science Foundation Grant 2102916. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

[1] Protocol for collecting Hydra from fresh water: https://www.protocols.io/view/hydra-collecting-for-citizen-scientists-14egnzonpg5d/v3

[2] Low-cost methods for maintain Hydra cultures: https://www.protocols.io/view/low-cost-methods-for-hydra-care-b645rgy6

[3] Commercially available live Hydra at EduScience UK: https://eduscienceuk.com/product/live-hydra-species-10-pack/

[4] Commercially available live Hydra at Blades Biological: https://blades-bio.co.uk/shop/living-organisms/pond-life/hydra-species-x-100/

[5] Commercially available live Hydra at Carolina Biological Supply: https://www.carolina.com/invertebrates/hydra-culture-living/132800.pr

[6] Wagner G (1905) On some movements and reactions of hydra. J. Cell Sci. 48: 585–622. doi: 10.1242/jcs.s2-48.192.585

[7] Lewbart GA, Zachariah TT (2023) Aquatic and terrestrial invertebrate welfare. Animals 13: 3375. doi: 10.3390/ani13213375

[8] Teaching material on macroinvertebrates and indicators of water quality: https://serc.carleton.edu/sp/mnstep/activities/35675.html

[9] Teaching material on how to determine the health of an aquatic ecosystem by identifying its macroinvertebrates: https://serc.carleton.edu/sp/mnstep/activities/35675.html

I think this article provides many ideas for going into details, reworking and exploring very interesting connections across various fields, even if, at first sight, they seem very distant from science. These connections can intrigue students and make them passionate about the topic. First of all, there is the influence of the environment on living beings and how even the simplest invertebrates try to react in order to survive. Another aspect to be explored is the regenerative capacity of tissues and its applications in the medical field. Students can also research other model organisms used in science and find out what they might be useful for. In my opinion, it is also very interesting to involve students in searching for other meanings and connections of Hydra in the mythology and in the modern world (e.g. Poliwag, Poliwhirl, Poliwrath, and Politoed: these Pokémon are inspired by the freshwater Hydra)

Cinzia Grazioli, Italy

Meet the planarian, a fascinating flatworm with incredible biological abilities and unique and surprising ways to respond to various stimuli.

Get a glimpse into the weird and wonderful life on Earth with the three winning entries in the Science in School writing…

Using pond snails as a low-cost, hands-on model to teach biology and environmental science in secondary schools.