Supporting materials

Explanation of the watt balance (Word document)

Explanation of the watt balance (PDF file)

Download

Download this article as a PDF

We all know what a kilogram is – or do we? Researchers worldwide are working to define precisely what this familiar unit is.

How much does it weigh? What is its surface area? What is its temperature? These questions may seem simple but the answers only make sense when we have defined a value and a unit.

The more widely accepted this unit is, the better the measurements are understood. Just imagine – if I walked seven furlongs to work this morning and you travelled 10 km, who had the longest journey? This is why we need an international system of units.

The first unit to be internationally defined was the metre (figure 1). It also led to the first international agreement on units, when the 1875 Convention of the Metre in Paris, France, established the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM, or Bureau International des Poids et Mesures) – an organisation that exists to this day.

Initially, the only common units were for length and mass, but the system has evolved over the years. Thus the initial set of units for length and mass was extended to include the standards of electricity, photometry and radiometry, ionising radiation, time and chemistry. The complete set of standardised units is referred to as the International System of Unitsw1 (SI for Système International d’Unités).

The SI is based on the metric system and consists of both base units and derived units. The seven base unitsw2 define a system of independent quantities and their units (see box on definitions of SI base units). The derived units of the SI define all other quantities in terms of the base units. For example, the SI unit of force, the newton, is defined as the force that accelerates a mass of one kilogram at the rate of one metre per second squared.

A universal set of units has clear advantages, but there is still some way to go before the SI is established globally and to the exclusion of all other systems. Initially established by 17 countries, the BIPM now has 55 member states. Nonetheless, the degree to which the SI has been adopted varies between the members. In both the UK and the USA, for example, miles, pints, and degrees Fahrenheit are still commonly used. Furthermore, even in fully metrified countries, some non-SI units remain popular. These include the minute, day and hour, as well as the hectare, litre and tonne.

The kilogram is the only one of the seven base units to have a prefix (‘kilo’) in its name. It is also the only one that is still officially defined by a material artefact – all others are defined by fundamental constants or atomic properties (see box on definitions of SI base units). The international prototype of the kilogram is a cylinder of platinum-iridium alloy, machined in 1878 and preserved at BIPM (figure 2).

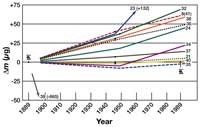

Over the years, several official copies have been produced and distributed to various national metrology offices (metrology is the scientific study of units and measurement). With the aid of modern technology, the mass of the prototype and its copies can now be compared with very high precision (up to 1 microgram), revealing significant variation (figure 3).

It is, therefore, high time for an absolute definition of the kilogram. This will not involve changing the mass of the kilogram. What will change is the way in which the kilogram is defined: rather than being defined as the mass of an object stored in a Paris vault, it will be a reproducible definition based on atomic properties and fundamental constants. Using this new definition, a well equipped laboratory will be able to create from scratch, without reference to the prototype, an object that weighs exactly 1 kg. Or, of course, to test and calibrate scales very precisely.

Furthermore, redefining the kilogram will also affect three other base units: the ampere, the mole and the candela, the definitions of which depend on the kilo (see box on definitions of SI base units).

Since the 1990s, several approaches have been pursued, two of which seem promising. Both involve defining the kilogram in terms of an invariant natural quantity: in one case the Avogadro constant, in another, the Planck constant. Both of the approaches also involve measuring the relevant constant to an unprecedented degree of precision.

| Base quantity | Base unit | Definition according to the International Committee of Weights and Measures (CGPM) | Date of the current definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | Metre (m) | The length of the path travelled by light in a vacuum during a time interval of 1/299 792 458 of a second | 1983 |

| Mass | Kilogram (kg) | The mass of the international prototype of the kilogram | 1901 |

| Time, duration | Second (s) | The duration of 9 192 631 770 periods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of a caesium-133 atom | 1967/68 |

| Electric current | Ampere (A) | That constant current which, if maintained in two straight parallel conductors of infinite length, of negligible circular cross-section, and placed 1 m apart in vacuum, would produce between these conductors a force equal to 2 x 10-7 newton per metre of length | 1946 |

| Thermodynamic temperature | Kelvin (K) | The fraction 1/273.16 of the thermodynamic temperature of the triple point of water | 1967/68 |

| Amount of substance | Mole (mol) | The amount of substance of a system which contains as many elementary entities as there are atoms in 0.012 kg of carbon-12 | 1971 |

| Luminous intensity | Candela (cd) | The luminous intensity, in a given direction, of a source that emits monochromatic radiation of frequency 540 x 1012 hertz and that has a radiant intensity in that direction of 1/683 watt per steradian | 1979 |

The aim of the international Avogadro project is to define the kilogram as the mass of a specific number of carbon-12 atoms. Under the current definition, Avogadro’s number is the number of atoms in 0.012 kg of carbon-12. Thus if we rearrange the equation, we could define a kilogram as the mass of an Avogadro number of carbon-12 atoms x 1000 / 12.

To do this, the project team aims to measure the value of the Avogadro constant (NA, which has the same numerical value as the Avogadro number, expressed in moles) more precisely than ever before.

At the heart of the project is a nearly perfect sphere of silicon (figure 4) weighing exactly 1 kg, as defined by the platinum-iridium prototype. Silicon, rather than carbon-12, was chosen because large, high-purity and almost perfect single crystals can be produced.

The scientists are using a variety of techniques to determine the distance between atoms (the lattice parameter), the crystal density and the mean molar mass of the silicon (which has several isotopes). Using these data, they will be able to calculate the number of atoms in the 1 kg silicon sphere and derive a new and more precise measurement of the Avogadro constant. This could then be used in a new definition of the kilogram (Andreas et al., 2011; Becker et al., 2003):

1 kg = atomic mass of C-12 x 0.0012 x NA

The other approach to defining the kilogram uses a watt balancew3, w4. The watt balance, which compares mechanical and electrical energy, was invented in 1975 and used in the 1980s to better determine the Planck constant by weighing the platinum-iridium prototype of the kilogram. Then scientists realised they could turn the idea around and use the instrument to define the kilogram.

Currently, the Planck constant has been measured to be:

h = 6.626 068 96 x 10-34 kg m2 s-1

The values of fundamental constants, such as the Planck constant, are invariants of nature. However their numerical values (e.g. 6.626 068 96 x 10-34) depend on the units (e.g. kg, m, and s) in which they are expressed. Fixing the numerical value of the constant therefore defines the units. In the case of the Planck constant, the metre and second are already defined in the SI. As can be seen in the equation above, therefore, precisely measuring the Parisian kilogram prototype – as will be possible with the watt balance – will allow h to be measured more precisely than before. Once that value is fixed, the kilogram can then be defined in terms of h, m and s, independently of the original prototype.

Worldwide, several metrology institutes are working to develop increasingly precise watt balances. One project, led by the Swiss Federal Institute of Metrology (METAS), includes CERN (see box), which is developing a type of magnetw3 that is crucial to the operation of the balance. The aim of all the watt balance projects is to reach a new definition of the mass unit – known provisionally as the electronic kilogram – by reducing the uncertainty in their experimental setups to ≤ 5 x 10-8. This, however, is no mean feat, due to the precision of the measurements and complexity of the instruments required.

So which of the two approaches will be used to redefine the kilogram? At the BIPM’s 24th general conference on weights and measures in 2011, it was proposed that the definition based on the Planck constant should be used. Nonetheless, if the proposal were accepted, the work on the Avogadro constant would not go to waste. For one thing, the Avogadro constant may be used in a new definition of the molew5. And for another, the Avogadro constant provides an alternative method to determine the Planck constantw6 – thus indirectly feeding into the definition of the kilogram. But that is another story.

The European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN)w7 is one of the world’s most prestigious research centres. Its main mission is fundamental physics – finding out what makes our Universe work, where it came from, and where it is going.

CERN is a member of EIROforumw8, the publisher of Science in School.

The authors would like to thank Simon Anders, a physicist based at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, for his helpful comments on the article.

This article highlights the importance of having and using an international system of units. It could be very suitable for introductory lessons in physics or chemistry, and could also be used in non-scientific subjects such as languages and history to explain how important it is to follow established conventions (e.g. grammar).

Before reading the text, the following questions could be asked to students to make them start thinking about the concepts explained in it:

As the article includes some historical data of the evolution of the international system of units, it could be used for a discussion of the history of science, a topic rarely seen in secondary school. Moreover, these historical details could make students who are not usually keen on science read the article with interest.

Mireia Güell Serra, Spain

Explanation of the watt balance (Word document)

Explanation of the watt balance (PDF file)

Download this article as a PDF