Supporting materials

Supporting information on the placebo effect (Word document)

Supporting information on the placebo effect (PDF file)

Download

Download this article as a PDF

When your doctor prescribes you a tablet and you get better, was it really the drug or could it have been the colour of the tablet? Andrew Brown investigates the placebo effect.

In 1796, the American doctor Elisha Perkins patented his ‘Perkins Tractor’, which he claimed could ‘draw off the noxious electrical fluid that lies at the root of all suffering’. Consisting of two metal rods, the device was waved over the patient’s body. Reports of its curative powers caught the attention of British doctor John Haygarth who, in controlled experiments, showed that although the Perkins Tractor did indeed alleviate symptoms, so did a wooden copy. He was the first to show that a therapeutic response can be achieved by something pharmacologically inert – what we now call the placebo effect.

The placebo effect is often considered to be a psychological rather than a physiological phenomenon – patients only think they are better. But it is far more than that, as clinical trials have testified. In a Swedish trial of heart patients, for example, those in the placebo control group were given an identical pacemaker to those in the treatment group, but unbeknown to them, the device was switched off. After three months, astonishingly, the symptoms of patients in both groups had improved. More astonishing still, the researchers were able to measure the improvement in the patients in the placebo control group as an increase in the flow of blood from the heart (Linde et al., 1999).

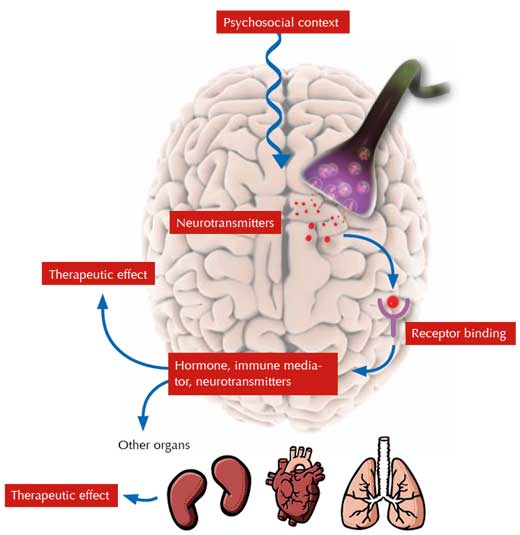

So what is going on? As Fabrizio Benedetti, professor of physiology and neuroscience and a world authority on the placebo effect, explains: “the placebo effect is a real neurobiological phenomenon, where something happens in the patient’s brain”. It is triggered not by the ingredients of the placebo itself, but by what it symbolises. In a clinical setting, there are many symbolic factors, which Benedetti refers to collectively as the ‘psychosocial context’ (Figure 1): “The sight and words of the doctor, the smell of the drugs, the hospital machinery: all of these sensory and social stimuli tell the patient that the therapy is being performed.” The patient’s resulting expectation of a therapeutic effect elicits the placebo effect.

But the psychosocial context can also determine the strength and type of placebo effect. For example, the number, colour and even the packaging of tablets influence their effects (for details of the research behind these observations, see the online supporting informationw1). In a US study in which half of the participants were given an inert sugar pill and half were given sham acupuncture (the needles did not actually pierce the skin), the sham acupuncture was significantly better at relieving pain than the sugar pill, whereas the pill helped patients sleep (Kaptchuk, 2006).

So how does the psychosocial context cause neurobiological changes in the brain? When a patient expects a therapeutic treatment, neurotransmitters are released. These bind to their corresponding receptors, prompting the release of further molecules in the brain and other organs, among them hormones, immune mediators and more neurotransmitters, which all cause far-reaching physiological changes that can generate a therapeutic effect.

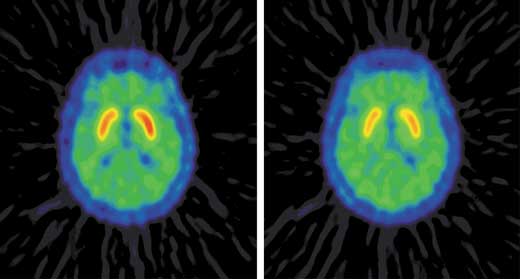

Benedetti’s work on pain and motor-related disorders illustrates that the neurobiological changes can take many forms: “If you expect a reduction in pain, you release endogenous opioids. If you expect a motor improvement, you release a completely different neurotransmitter, dopamine” (Figure 2).

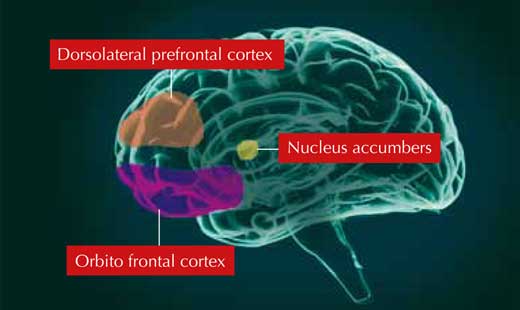

“But the crucial question” explains Benedetti, “is how what the brain expects can trigger a specific release of neurotransmitters.” At present, he admits that we have no definitive answer to this, but two mechanisms have been studied particularly closely (Figure 3):

Both the anxiety and reward networks control many biochemical pathways and associated organs. In the switched-off pacemaker study, the heart condition of the patients in the placebo group is thought to have improved because they were less anxious and produced lower levels of catecholamine stress hormones, known to alter heart function.

Placebo research is still in its infancy; perhaps the most exciting future research will focus on the placebo effect in conventional medicine. Benedetti has already begun, looking at the placebo effect of real drugs. For example, in one trial, he found that an injection of the powerful analgesic metamizol was effective in reducing patients’ post-operative pain, whereas a hidden administration of the drug (via a pre-laid tube) was completely ineffective (Colloca & Benedetti, 2005). The analgesic effect of the open injection was therefore entirely due to the placebo effect.

This is revolutionary: the idea that the efficacy of drugs can be affected so profoundly by the context in which they are given. For the medical profession, the challenge will be to make the most effective and ethical use of the placebo effect.

This article is based on an interview and a lecturew2 given at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), in Heidelberg, Germany, by Fabrizio Benedetti, professor of physiology and neuroscience at the University of Turin Medical School and at the National Institute of Neuroscience in Italy.

Although the word ‘placebo’ is probably familiar to most people, the chances are that not many really know what it is. The author helps the reader to understand what the placebo effect is and what it does, including the complex ways in which it helps patients get better.

This article will be of most benefit to the study of the nervous system in upper secondary-school biology. The suggested classroom activities will be particularly useful for teachers. The questions provided would be suitable for biology students in whole-class discussion sessions, small-group projects or even individual homework assignments. Since the content of the article is not purely scientific but also touches on ethical issues, it could provide excellent discussion material for psychology and social science classes.

Michalis Hadjimarcou, Cyprus