Supporting materials

Download

Download this article as a PDF

Mendelian inheritance can be a tricky topic to teach, but Pat Tellinghuisen, Jennifer Sexton and Rachael Shevin’s memorable dragon-breeding game makes it easier to understand and remember.

Dragons may be mythical animals, but they can still be good tools for investigating Mendelian inheritance. In the following activity, students will ‘breed’ baby dragons, using paper chromosomes to determine the genotype and phenotype.

The activity has been tested with students aged 12-13, and generally takes one lesson – about 45 to 60 minutes.

The chromosome strips, Tables 1-3 from the worksheet, the worksheet itself and the basic dragon drawing can be downloaded from the Science in School websitew1.

Using the information below, introduce the dragon story and the required background for the activity to the students. Then hand out the materials and let the students follow the instructions on the student worksheet. Tables 1–3 can also be downloaded from the Science in School websitew1.

Dragons are a curious type of creature. Amazingly, though, their genetics is very similar to that of humans – or even guinea pigs. Many schools keep pet guinea pigs, but wouldn’t it be much more exciting to keep a herd of dragons? Unfortunately, dragons are very expensive, so your school can only afford two – one of each sex. The purpose of this activity is to determine what kinds of dragon you could have in your herd when (or if) your two dragons decide to mate.

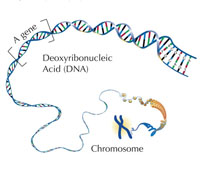

Each cell in all living organisms contains hereditary information that is encoded by a molecule called deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA): show students the DNA model. DNA is an extremely long and skinny molecule, which when all coiled up and bunched together, is called a chromosome: show students the picture of a chromosome. Each chromosome is a separate piece of DNA, so a cell with eight chromosomes has eight long pieces of DNA.

A gene is a segment of the long DNA molecule. Different genes may be different lengths and each gene is a code for how a certain polypeptide should be made. One or more polypeptides form a protein, which can generally be sorted into two different types: those that run the chemical reactions in your body (enzymes), and those that are the structural components of your body (structural proteins). How an organism looks and functions is a result of the cumulative effect of both these types of protein.

Any organism that has ‘parents’ has an even number of chromosomes, because half of the chromosomes come from the ‘father’ and the other half from the ‘mother’. For example, in plants, a pollen grain is the paternal contribution and an ovule is the maternal contribution. These two cells combine to make a single cell, which will grow into a seed (the offspring).

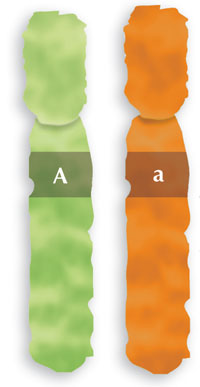

Humans have 46 chromosomes, sorted into 23 pairs. One chromosome in each of the 23 pairs is from the person’s father, the other from his or her mother. Since chromosomes come in pairs, genes do too. One gene is located on one member of the chromosome pair; the other gene is in the same location on the other chromosome. The gene ‘pair’ is technically referred to as a ‘gene’, as both members of the pair encode the same trait. For any gene, a variety of different forms – known as alleles – may exist, but each person can have a maximum of only two alleles (one from the mother, and one from the father). The two copies of the gene that a person has may be the same or different alleles.

Our dragons have 14 chromosomes in seven pairs, and we will look at only one gene on each of the pairs. We will be investigating seven different traits (e.g. the ability to breathe fire), each of which is controlled by a single gene – we say that such a trait is monogenic. Each of the seven genes has two alleles.

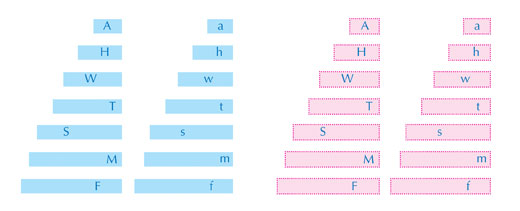

One set of 14 strips represents the chromosomes from the mother (female) dragon. The other, differently coloured set, represents the chromosomes from the father (male) dragon.

Each chromosome strip has a letter, which may be either upper or lower case. The upper-case letters represent dominant alleles, and the lower-case letters represent recessive alleles. Each pair of letters codes for a trait. If at least one dominant allele (upper-case letter) is present, the dominant trait will occur (e.g. the dragon can breathe fire); the recessive trait (e.g. inability to breathe fire) will only occur if the dragon has two copies of the recessive allele.

The traits encoded by the letters are as follows:

| Male gene (blue) | Female gene (pink) |

|---|---|

To introduce the concept of codominance, you can extend the activity by swapping the relevant materials concerning the body colour trait (genotype Aa) for the following ones with the genotypes A/Ä/a, where A and Ä are codominant and a is recessive:

| Genotype | Phenotype |

|---|---|

| AA or Aa | Blue body and head |

| ÄÄ or Äa | Black body and head |

| AÄ | Stripy blue and black body and head |

| aa | White body and head |

| Trait | Genotype | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| Body colour (A/Ä/a) |

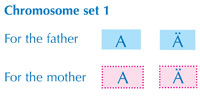

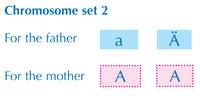

You will need to replace the A/a chromosome stripes by two different sets of parents to achieve offspring with all six possible genotypes. Half of your class should get set 1, the other half set 2.

Instead of drawing dragon parts, you could have your students draw other mythical creatures, or even build them, for example from marshmallows and pins (see Soderberg, 1992).

This activity is based on an idea by Patti Soderberg, adapted with permission from The Science Teacher (see Soderberg, 1992). Her reebops lesson was then adapted by the authors. Credit for the chromosome strips goes to Nancy Clarkw2, and Marlene Rau, editor of Science in School, included the codominance example.

As a secondary-school biology teacher I had never come across the idea of teaching genetics using mythical creatures, but after my initial surprise, I realised that using the genetics of dragons was perfectly coherent with the scientific facts… and really good fun! The idea of randomly choosing genes and looking for the resulting traits of baby dragons is ingenious and effective at the same time.

Even if they aren’t real, dragons can help to raise interest in a topic generally considered boring (at least by students) and can convey scientific concepts as well as real organisms like Mendel’s peas do.

I recommend this article to primary- and lower-secondary school biology teachers willing to address the basics of Mendelian genetics (genes, alleles, genotype and phenotype, dominance, meiosis and breeding) in a novel and playful way. The activity could be carried out very easily in the classroom with practically no equipment.

Suitable comprehension questions include:

Giulia Realdon, Italy

Download this article as a PDF