Ginger beer: a traditional fermented low-alcohol drink Teach article

Because of its low alcohol content, ginger ‘beer’ is a popular drink with British children. Dean Madden from the National Centre for Biotechnology Education, University of Reading, UK, gives his recipe for introducing younger students to the principles of fermentation, food hygiene and the…

The predecessors of modern carbonated soft drinks were often brewed at home. In late 19th century Britain, ‘small beers’ were fermented drinks with a very low alcohol content. These were usually safer to drink than water, which was often contaminated.

Ginger beer originated in England in the mid-1700s and was exported worldwide. This was made possible by the use of strong earthenware bottles that were sealed by a liquid- and gas-tight glaze (called ‘Bristol glaze’). The British Excise Regulations of 1855 required that the drink contained no more than 2% alcohol, and usually it was far less potent: hence ginger beer became popular with children. By the start of the 20th century it was produced commercially in almost every town in the United Kingdom. The ‘beer’ was often sold by street hawkers, and it was sometimes dispensed from a ‘beer engine’ – an elaborate device like an upright piano with beer pump handles that was pulled through the streets by a pony.

In 1935 there were more than 3000 producers of ginger beer in the United Kingdom: today, however, only one British firm makes a traditional brewed product – modern ‘ginger beer’ is usually made with flavourings and carbonated with pressurised carbon dioxide.

There are many recipes for ginger beer; the basic ingredients are ginger, lemon, sugar and yeast. Real ginger beer is made from fresh root ginger (Zingiber officinale), often with other flavourings such as juniper (Juniperus communis), liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) or chilli (Capsicum annuum) – which gives the product extra ‘bite’. Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) is sometimes used to inhibit bacterial growth (as it was in normal beer before the introduction of hops). Jamaican ginger beer is sometimes made with lime instead of lemon juice.

The following recipe is for one litre and can be scaled up and changed as required – some suggest that the ginger should be grated rather than sliced and crushed. Others recommend boiling the mixture before adding the yeast, to extract more flavour from the ingredients.

| Compound | Source | Relative strength |

|---|---|---|

| Piperine | Black pepper | 1 |

| Gingerol | Fresh ginger | 1.8 |

| Shogaol | Dried ginger | 1.5 |

| Zingerone | Cooked ginger | 0.5 |

| Capsaicin | Chilli | 150-300 |

Equipment and materials

Equipment

- Sharp knife and chopping board

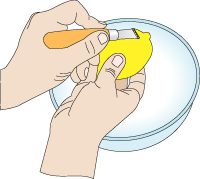

- Lemon zester or grater

- Lemon squeezer

- Rolling pin

- Large spoon

- Kettle for boiling water

- Thermometer

- Large bowl or jug

- Clean tea towel to cover bowl

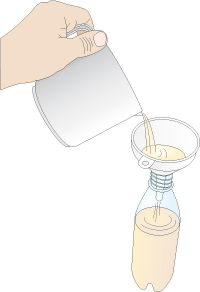

- Sieve and funnel for straining liquid into bottles

- Plastic (PET) bottle and cap. Do not use glass bottles!

Materials

- 1 l water

- 150 g root ginger (~130?g when peeled)

- Medium-sized lemon (preferably unwaxed)

- 140 g sugar (brown or white)

- 4 g cream of tartar (tartaric acid)

- 4 g dried ale or bread yeast, or 8 g fresh

- Sterilising solution suitable for food use

- Strong plastic bag in which to bruise ginger

- Optional: Other spices such as chilli, nutmeg, liquorice, vanilla, cardamom, cloves, juniper, fennel, coriander, star anise

Method

- Peel the ginger and cut it into slices 3–5 mm thick. Bruise the slices well by placing them in a strong, clean plastic bag and crushing them with a rolling pin.

- Place the ginger in a large bowl or jug. Scrape the lemon zest over it, then add the juice from the lemon.

- Place the remaining ingredients except for the yeast in the bowl, then carefully pour on boiling water. Stir.

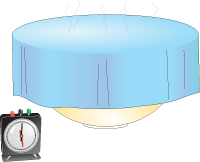

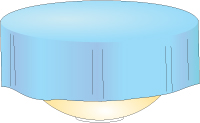

- Cover the bowl with a clean cloth and leave the liquid to cool to 25–30 °C (this can take 60–90 min).

- While the liquid is cooling, sterilise the PET bottles using the sterilising solution. Ensure that the bottles are thoroughly rinsed with clean water after sterilising.*

- Add the yeast to the warm liquid in the bowl and stir until it has dispersed.

- Cover the bowl with a clean cloth and leave it in a warm place for 24 h.

- Skim off the yeast, leaving the sediment in the bowl. Strain into the sterilised plastic bottles, leaving a 3–5 cm air gap at the top.

- IMPORTANT! Allow the beer to ferment at room temperature (~21 °C) for no more than 48 h, then place the bottles in a fridge. Drink within six days.

* There is no need to use boiled water to rinse the bottles after sterilisation. The sterilising step is to get rid of major contaminants left in reused bottles. The tap water used for rinsing should not introduce contaminants, and should it do so, they will be quickly out-competed by the relatively large inoculum of yeast. The low pH of the liquid (from the lemons) will also prevent bacteria (although not yeast) from growing.

Safety and other concerns

Glass bottles must NEVER be used, as the gas produced will cause them to explode. This drink should always be made in plastic bottles, and it should always be refrigerated and consumed within six days. The short fermentation period and refrigeration ensure that the alcohol content of the drink remains low.

Please remember that some religious groups object even to the consumption of products that contain little or no alcohol but have been produced by brewing. The students may, however, be happy to take part in the practical without drinking the resulting ginger beer. Teachers should be sensitive to such concerns.

Preparation and timing

It takes approximately 90 minutes to prepare the drink, including a cooling period of 60 minutes. The initial fermentation takes 24 hours, followed by up to 48 hours fermentation in bottles. The bottles can be sterilised in advance if desired.

Additional investigations

This practical activity can be used as the starting point for other practical investigations, some of a technological nature. These include:

- Most fermented soft drinks are acidified to inhibit bacterial growth. Does this also inhibit the yeast? Investigate the effect of pH on the rate of fermentation (12 g of citric acid is roughly equivalent to adding the juice of one lemon).

- Some flavourings, such as cinnamon, cloves and yarrow, are thought to inhibit the growth of microbes. Devise an experiment to test this. What are the implications of your findings for the recipes and methods of soft-drink production?

- In the USA, sachets of dried herbs and spices were sold so that people could make ‘root beers’ at home. Could similar kits be devised for ginger beer? How could you prepare and package the ingredients so that they were convenient for home users?

- How could you measure and control the alcohol content of a fermented drink, to ensure that it was not excessive?

- Homemade ginger beer contains live yeast. Consequently, it has a short shelf life and there is a danger that the bottles might explode. Investigate ways of overcoming this problem. These might include one or more of the following:

- Selling the product as a fresh drink that has to be stored under refrigeration

- Filtering the yeast from the drink before bottling it

- Precipitating the yeast with a fining agent before bottling

- Pasteurising the drink before bottling, to kill the yeast

- Adding a chemical preservative to the drink to kill the yeast

- Using a type of yeast that precipitates (flocculates) naturally

- Increasing the sugar content of the finished drink so that the yeast cannot grow (due to osmosis)

- Designing a special bottle that allows excess gas to escape while maintaining the fizz and preventing contamination of the drink.

Suppliers

All of the materials required to make ginger beer can be bought from a supermarket, market or a supplier of wine-making equipment.

Note, however, that ginger beer was traditionally made not with pure yeast, but with a mixed culture of lactobacilli and yeasts that is sometimes called a ‘Ginger beer plant’ or a ‘Beeswine’ culture. This is similar to a kefir culture and can be maintained and passed on to others who wish to make ginger beer.

The ‘ginger beer plant’ was described in:

Ward HM (1892) The ginger beer plant and the organisms composing it. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B 183: 125–197

According to the UK National Collection of Yeast Cultures (www.ncyc.co.uk/beeswine.php), the only safe commercial source of this culture in Europe is now the German culture collection, DSMZ. They have a special education price for this culture, DSMZ No. 2484 (www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/html/strains/strain.dsm002484.html).

Resources

- For an excellent recipe book for non-alcoholic fermented drinks, see:

- Cresswell SE (1998) Homemade root beer, soda, and pop. Pownal, VT, USA: Storey Books

- It includes hints on bottling, cleanliness and the production of concentrates from raw ingredients.

- A large, world-renowned and authoritative text on all aspects of food culture and chemistry is:

- McGee H (2004) On food and cooking, 2nd ed. London, UK: Hodder and Stoughton

- For Wikipedia’s webpage on ginger beer, see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ginger_beer

- For the Yahoo! group webpage on ginger beer plants, see: http://health.groups.yahoo.com/group/GingerBeerPlant/

Review

When I was at school there always seemed to be some lad with a ginger beer plant in his desk – woe betide him if it exploded! This interesting and excellent article describes how ginger beer can be made simply without a ginger beer plant, using everyday items.

The practical can be used to complement different levels of scientific understanding from basic sterility to fermentation, respiration, microbial growth and the effect of pH on microbial growth. The additional investigations suggested in the article would make excellent individual projects for students aged 16-18 or group projects for younger students. Students could be encouraged to make a small poster on the antimicrobial activity of a spice as well as investigating it practically. More advanced students could investigate chilli strength and the chemical components of capsaicin. The wide range of activities this practical offers means that it could be used several times with both the same and different groups of students.

Shelley Goodman, UK