Supporting materials

How genetic fingerprinting is used in forensic casework (Word document)

How genetic fingerprinting is used in forensic casework (PDF file)

Download

Download this article as a PDF

In popular TV detective series, genetic fingerprinting is commonly used to identify criminals. Sara Müller and Heike Göllner-Heibült take a look behind the scenes.

The idea of distinguishing people by their genetic characteristics is not new. Discovered in 1900 by Karl Landsteinerw1, ABO blood typing was the first genetic marker to be used in forensics, later complemented by MN blood groups (1927) and the Rhesus factor (1937).

Even when we analyse all three blood group systems simultaneously, however, about one in ten people give identical results; this is what makes blood transfusions possible. For forensic purposes, however, it is a disadvantage: the results may tell you that your blood sample does not come from Suspect X, but they cannot tell you with any acceptable level of certainty that it does come from Suspect Y.

Advances were made in the 1970s and 80s, with the analysis of different forms of enzymes (isoenzymes) in red blood cells and blood serum. The certainty that the sample really came from the suspect depended on the number of proteins analysed (usually four); we call this certainty the power of discrimination. The power of discrimination that these combined techniques offered was still only 1:1000, better than the 1:10 power of blood group analysis, but still not good enough. To get a better power, we needed to take a closer look at our genetic composition.

The human genome consists of 46 paired chromosomes: 23 from our mother, 23 from our father. We therefore have two of each chromosome (except – in the case of men – sex chromosomes) and thus two copies of each gene.

The main component of chromosomes is deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), which contains information for building the proteins we need for life. However, of our 3 billion base pairs (bp), only about 4% actually code for proteins; the rest is often just ‘filling’ consisting of repetitive sequences organised in clusters. If you compare the DNA of two humans, most of it is identical, with the variability found largely in these repetitive sequences.

Different people can have different numbers of repetitions of these sequences: one person may have five repeats at a specific DNA locus (site); another person may have seven. Using samples, e.g. from blood or semen, we can analyse the repetitive sequences at several DNA loci; we call this analysis a genetic fingerprint. Like fingerprints, genetic fingerprints can be used to distinguish individuals.

Although the term ‘genetic fingerprinting’ (or genetic profiling) is commonly used, not everybody is aware that it actually encompasses two very different techniques, only one of which is commonly used in forensics today.

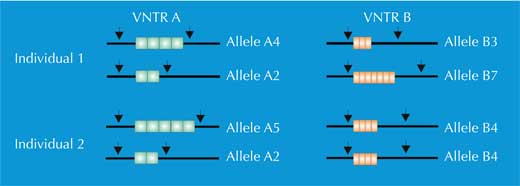

The first method of genetic fingerprinting was invented in 1984 by Alec Jeffreysw2, who used repeated DNA sequences known as variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs; e.g. sequence D1S80, (AGGACCACCAGGAAGG)n). These sequences, 10-100 bp per repeat, can be investigated using restriction enzymes, which work like molecular scissors to cut the DNA at defined sequences (recognition sequences). In our entire genome, a 6 bp recognition sequence will occur around 730 000 times.

This means that if you cut the genome with a particular restriction enzyme, you will get around 730 000 restriction fragments of varying lengths. And this is where the VNTRs become important: the number of repeats in a particular VNTR cluster may vary between individuals, which means that the length of the corresponding restriction fragment will vary between individuals too (Figure 1). We call this phenomenon restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP).

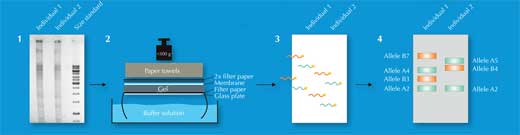

Of the 730 000 restriction fragments, only some will differ between individuals – too few to be detected by eye. Instead, scientists used a technique called Southern blotting, which allowed only the sequences of interest to be visualised. To do this, they separated the restriction fragments according to size by gel electrophoresis, using an electric current to pull the charged molecules of DNA through a gel. The distance travelled was determined by the fragment size (Figure 2, Step 1). Next, they transferred the DNA to a membrane (Figure 2, Step 2) and applied a radioactively labelled probe that was complementary to the VNTR(s) of interest. The probe hybridised (stuck) to the matching sequences (Figure 2, Step 3) and by placing the membrane on an X-ray film, the scientists got a picture of the radioactively labelled bands, each of which represented a different length of fragment (Figure 2, Step 4). This picture was the genetic fingerprint.

So how many VNTRs needed to be compared to reliably distinguish between individuals? If the scientists chose VNTRs with enough variation (e.g. D1S80, which may be repeated anything from 15 to 41 times), they only needed to compare four different VNTRs to have a power of discrimination of 1:1 million – much better than the 1:10 offered by ABO blood typing.

Kary Mullis’ invention, in 1983, of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) won him the Nobel Prize in Chemistryw3, w4. This invention, together with the discovery in the late 1980s of short tandem repeats (STRs) – 2-9 bp repeated sequences, also called microsatellites – paved the way for the high-speed genetic fingerprinting technique that forensic scientists use today.

PCR enables a DNA locus of interest (e.g. the 4 bp STR known as D18S51, (AGAA)n), to be amplified exponentially, generating a billion copies of a single DNA molecule in a few hours (Figure 3). For forensic scientists, this has the advantage of making the analysis of even very tiny samples possible – as few as 30 cells (see Table 1 for a comparison with RFLP-based genetic fingerprinting).

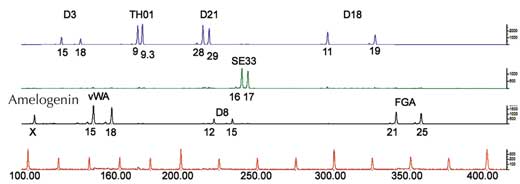

For PCR analysis, we need STRs flanked by sequences that are identical in all human beings (we say these sequences are conserved). We then use primers – short molecules that are complementary to the conserved flanking sequences (genes 1134 and 1135 in Figure 4) – to initiate the PCR. Once the DNA has been amplified, we can separate it either by gel electrophoresis (Figure 5) or, in modern forensic science, by electrophoretic automated sequencing (Figure 6), and visualise it as a genetic fingerprint.

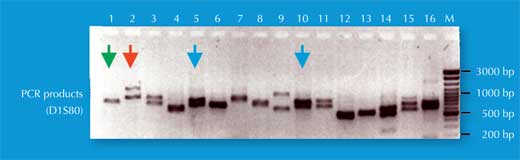

We have two copies of each chromosome, so we also have two copies of each STR. If, for each copy of the STR, someone has the same number of repetitions (i.e. the same allele), the PCR analysis reveals only one size of DNA fragment: the person is homozygous for that STR allele (green arrow in Figure 5, corresponding to individual 2 in Figure 4). If the two chromosomes carry non-identical alleles for that STR, we see two sizes of fragment and say that the person is heterozygous (red arrow in Figure 5, corresponding to individual 1 from Figure 4).

If we only analyse one STR, the chance of two unrelated people having the same PCR-based genetic fingerprint is high – between 1:2 and 1:100 (blue arrows in Figure 5). This is because STRs have fewer alleles and lower heterozygosity than the VNTRs used in RFLP-based genetic fingerprints. To overcome this disadvantage, we analyse multiple STRs simultaneously; with 16 STRs, as is common in forensic casework in Germany, we can achieve a power of discrimination of 1:10 billion (equivalent to one person in the world’s population; (Figure 6).

| RFLP | PCR | |

|---|---|---|

| Amount of starting DNA | 30–50 µg | At least 200 pg (about 30 cells) for a complete STR pattern |

| Sensitivity | + | +++ |

| DNA quality required for analysis | Complete genome | No complete genome necessary; degradation products also sufficient because of the short sequences involved (total sequence length of an STR, including multiple repeats and flanking sequences, approximately 50– 500 bp) |

| Time | Days to weeks | Hours |

| Discrimination power per locus | +++ (More alleles and more heterozygosity per locus) |

+ (Fewer alleles and less heterozygosity per locus) However, multiplex PCR amplification (PCR with more than one pair of primers) and multi-colour labelling allows more than 16 loci to be examined simultaneously, which provides an excellent power of discrimination |

| Repeat unit | 10 bp to 100 bp | 2 bp to 9 bp (in forensic case work, mainly 4 bp) |

| Automated detection | Not possible | High-throughput sample processing possible |

| Number of validated loci (important if relatives are involved) | Limited number | Large number |

| Risk for contamination | + | +++ |

| Additional safety measures required? | Yes (because of radioactive probing) | No (no radioactive probing) |

We now know what genetic fingerprinting is, but how is it used? PCR-based genetic fingerprinting is widely applicable in forensic investigations: it enables the police to exclude or identify suspects on the basis of genetic material such as hair follicles, skin, semen, saliva or blood (see the story that can be downloaded beloww5). A genetic fingerprint alone, however, is not sufficient evidence for a conviction, as close relatives may have very similar fingerprints (and monozygotic twins will normally have identical ones).

And to complicate international forensic investigations, although there is a European recommendation to analyse 16 STRs, each country can decide which STRs to analyse, which makes comparisons difficult.

The PCR-based method is also used in humans for paternity testing, diagnosing many genetic diseases (e.g. Huntingdon’s disease), identifying disaster victims, tracing family trees, tracking down missing people and investigating historical figures (e.g. the last Tsar of Russia and his family). In other organisms, it can be used for conservation purposes (e.g. to analyse confiscated ivory), in drug investigations (e.g. by analysing seized cannabis plants), to control food or water quality (e.g. by identifying contaminating microbes), in medicine (e.g. to detect viral infections such as HIV, hepatitis or influenza) and in bioterrorism investigations (e.g. to identify microbial strains).

RFLP-based genetic fingerprinting, although largely obsolete due to the many advantages of the PCR method (Table 1), is still used for classifying plants and animals in basic research. It is particularly useful when there is insufficient information about the genome of the species – remember that for the PCR method, we need regions that vary widely between individuals and are flanked by conserved regions of known sequence.

The isolation of DNA at school gives the students a ‘wow’ moment when they realise that they are looking at the complete genetic information coding for an organism – a few cotton wool-like strands of DNA that were precipitated by alcohol. It is easy to perform at school using salivaw6 (or epithelial cells from commercially available kits), peas (Madden, 2006), tomatoes, onionsw7 or calf thymus (although check local restrictions on using calf thymus at school)w8.

Subsequent PCR of a specific STR in human DNA, for example D1S80 or TH01, can be performed at schoolw6, using reasonably priced commercially available kitsw9 if necessary. If your school has no access to a thermocycler, the thermocycling can be carried out in three water baths, although it is tedious and very hands-on.

If this equipment is not available, there are kits that both simulate and simplify the whole process of genetic fingerprintingw10. These kits contain fragments of DNA that simulate the amplification of different alleles of a single STR or VNTR. (In fact, they are restriction fragments of DNA from plasmid or lambda phage DNA.) The DNA requires electrophoresis and subsequent staining so that students are able to compare ‘amplified’ DNA sequences from a sample of evidence with those of several suspects. Of course, this is very different from detecting amplified STRs using electrophoretic automatic sequencing (and does not even accurately represent the visualisation of VNTRs using Southern blotting, as the DNA is stained directly on the gel), but it nonetheless demonstrates the principles of the analytical process. When using these simulation kits, the students should be made aware that the experiments give the impression that differences between individuals can be easily identified, which is not the case.

The authors would like to thank Wolfgang Nellen for his ideas about the article and for allowing the Science Bridge instructions to be made available free of charge.

They are also grateful to Shelley Goodman for her advice on using commercial kits at school.

The idea of using DNA to identify one individual in the world is mind-blowing. The genetic fingerprinting of an individual relies on the sequences are that not used in coding, but how are these fingerprints created? This article explains.

The ability to identify criminals from DNA databases raises important questions: is it ethical to hold human DNA in such databases or is it a breach of human rights? Should there be a DNA fingerprint for every person or just those who are arrested? How long should the DNA profile be kept?

Students may wish to discuss how genetic fingerprinting can help diagnose genetic diseases, as well as its application in the fight against poaching and species extinction. Ideally they should be able to try the technique for themselves, either as a real or a simulated experiment.

Shelley Goodman, UK