Tell me about it: adventures in science communication Teach article

Scientists often need to communicate their subject to non-experts, such as policymakers and the public. This absorbing structured activity challenges school students to do the same.

As a science teacher, you have come across the term ‘science communication’, which describes the practice of communicating or sharing scientific knowledge with non-experts. This could be to explain the science behind a newsworthy issue such as a viral outbreak or the importance of vaccination.

Science communication modules have made their way onto most science degree courses, and I believe development of these skills should begin at school. What is the point of having scientific knowledge if you cannot share it with your peers and the public in an accurate and, if possible, enjoyable way?

Science communication at school

As a scientist and teacher, I have a strong interest in science communication. So, at our school in Larnaca, Cyprus, we have decided to integrate this growing field into our science curriculum – not only because many of our students go on to science-based careers, but also because many of the skills involved are valuable in most professions.

For the past 20 years, I have been working on ideas for developing my students’ research, writing and presentation skills within the science curriculum. One example of this is our programme that involves each of our students researching a given scientist, including their personal history and their contribution to science, then finally presenting the scientist in character and in costume at an open-school event we call the ‘Corridor of Scientists’. Although none of the individual stages of this programme is particularly novel, it is the progression through five stages that creates the programme’s success.

Koulla Andronicou

On this journey, students develop their skills in research and verbal and written communication. They also learn to distinguish science communication from how scientists communicate with their peers – all while hopefully being inspired by a scientist initially unknown to them!

In this article, I describe the five-stage process used at our school with students from 14 to 19 years of age. The programme has been designed to be carried out over a period of approximately one month, with each stage being assessed by the class science teacher. However, the process and timescale can easily be adapted to suit your needs and the resources available to your department. For example, if you have a cross-curricular programme in your school, other departments such as history or drama could also get involved.

Stage 1: Choosing a main theme

Decide on the main theme for the programme. This provides the selection principle for choosing the individual scientists.

Teachers can choose a theme specifically for this programme, or one that is linked to a wider school activity. Possible topics include:

- Living scientists (those alive today)

- Contemporary scientists (those working today)

- Scientists from a particular century (e.g. 19th century)

- Scientists from the students’ home country or specific region

- Scientists working on a particular scientific area or topic (e.g. space travel, the periodic table or the history of medicine)

Stage 2: Selecting a scientist

Each student is given a choice between two scientists related to the theme, and they have a week to decide which one they will research.

The teacher needs to provide the names of scientists for students to choose between, within the chosen theme. By not allowing the students to pick scientists for themselves, you are avoiding the usual influx of Einsteins and Marie Curies! Although the contributions made by such iconic individuals are indisputable, it is important to open our students’ horizons to significant but lesser-known scientists, both past and present. And by having a choice between two scientists, students still feel they have some control over the final outcome.

Put the choices in a sealed envelope for each student, together with the instructions for the whole programme. This creates an air of anticipation and excitement right from the start.

Christoforos Papachristoforou

Stage 3: Writing the biography

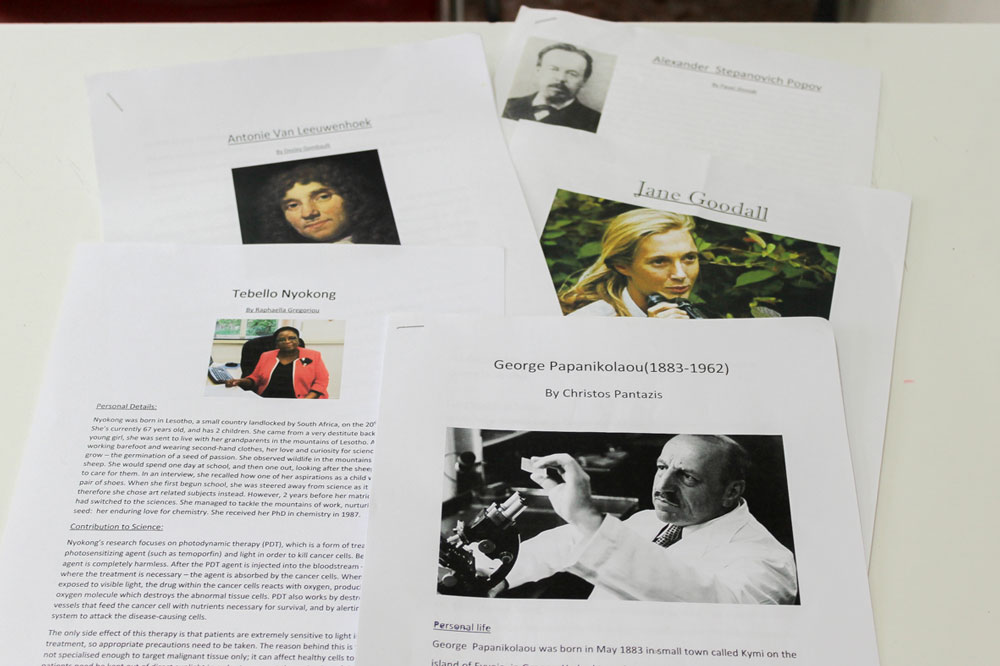

Students write a brief description of the personal history of their scientist and their main contributions to science.

In this stage, students attempt to use simple written language to explain more complex scientific ideas – a key skill for science communicators. In the process, they will need to select and evaluate different sources of information, and to reference those they use.

Each biography should include the following elements:

- A small photograph or other picture of the scientist

- A paragraph on their personal lives (up to 200 words)

- A simplified review of their most famous paper or most important scientific idea (up to 300 words)

- At least three references (the sources of information)

Make it clear to students that they must use their own words throughout. This is very important, as it helps to build an awareness of plagiarism (which can be partly unconscious) and how to avoid it. Encourage students to use original sources (such as scientific papers) where possible.

At this point, you can also discuss with the class how scientists share ideas through peer-reviewed scientific papers and conferences, which are not the same as science communication to non-experts. Instead, these activities are part of the way science itself operates, as the work of a scientist or research group is evaluated by other experts in the same field. The peer-review process ensures a scientific paper is approved by an impartial review panel before being published. It is essential for adding validity and credibility to research and maintaining high standards.

Christoforos Papachristoforou

Stage 4: Presenting to the class

Students give a 2–3 minute presentation in character to their classmates, who are encouraged to ask questions.

The presentation should include a brief introduction to the scientist’s life, followed by a simple explanation of one of the scientific ideas associated with them. Unlike the biography, it should be in the first person – for example, ‘I was born in May 1883 in the town of Kymi, Greece…’.

As this is an exercise in verbal communication to non-experts, students should be encouraged to speak just from a few notes, rather than read out a prepared speech. Each presenter should be allowed to use a board and marker at most – no props, no fancy computer graphics, just the power of speech!

Christoforos Papachristoforou

Stage 5: Presenting to the public

At the ‘Corridor of Scientists’ event, students dress up in character and host their own stands, where the ‘public’ can visit and ask questions.

This stage is most definitely the highlight of the programme for the students, who may have evolved from timid laypersons to confident science communicators and experts in their field!

The key idea for this stage is that it’s an open, public event, not a classroom activity. The event should be held in a suitable space – such as a school corridor or hall – so that visitors can move easily from one scientist to the next. Each student should have a table with a few simple items as prompts for discussion about their scientist. These items could include a flag, a few photographs, or equipment such as a microscope. Students, teachers, family and friends are invited to wander around the tables and ask the scientists about their lives and contributions to science.

Ashani Weeraratna, cancer scientist

Aristotle, ancient Greek philosopher and scientist

George Papanikolaou, Greek-American physiologist and inventor of the ‘pap smear’ test

Emmy Noether, German mathematician

Christoforos Papachristoforou, Koulla Andronicou

Ask some of the visitors – such as students from other classes or teachers not connected with science – to give their subjective feedback about the event to individual students and the teacher. After all, it is only the ‘public’ who can comment on whether the scientists’ attempts to communicate with them have been successful.

Instead of the ‘Corridor of Scientists’, you can use alternative titles for the event, such as the ‘Hall of Past Scientists’, where scientists are placed in chronological order like a journey through time. The possible variations are endless.

Resources

- Read a short article about what science communication is.

- Find out more about the many different aspects of science communication with these videos for science students and others.

- Enjoy reading some great popular-science articles and podcasts written by young scientists on the Naked Scientists website.

- Watch a video from EU Science & Innovation about why science communication is important for researchers.

- This comprehensive article gives useful planning and practical advice for would-be science communicators. See:

- Illingworth S (2017) Delivering effective science communication: advice from a professional science communicator. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology 70: 10-16. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.04.002

- Browse the Understand articles on the Science in School website for a huge range of accessible articles written mostly by scientists.

Review

This article describes an initiative to actively develop students’ ability to communicate their scientific knowledge, while also teaching them about how scientists communicate within science. In addition, the project encourages the development of ‘transferable skills’, such as information research and public speaking – as well as creative imagination.

Teachers could adapt the topics for the project to suit their own subjects. For example, biology teachers could choose scientists relevant to this area of science or a part of biology (e.g. genetics). The activity could also be cross-curricular, blending with English or history classes, or developed to include information technology in elements of the presentations.

‘The corridor of scientists’ event is also adaptable and could be used on its own or as part of a science fair, open day (or evening) or other event.

Marie Walsh, science lecturer, Ireland