Supporting materials

Analysis of the structure of Campbell (Word document)

Analysis of the structure of Campbell (PDF file)

Download

Download this article as a PDF

Learn how to use research articles in your science lessons.

Scientists use research articles to communicate their research findings and scientific claims. These articles are not just factual reports of experimental work; the authors also try to convince the reader that their argument is correct. It is now easier than ever to read the original research behind science stories in the media, as more and more articles are being made freely available through open-access publishing.

Reading research articles is an opportunity for secondary-school students to learn about:

Reading research articles is not an easy task for students, but they can find it inspiring. Here we describe a classroom activity that we have been using to teach students aged 15-16 years and older about the textual structure (part 1) and the argumentative structure (part 2) of a research article. This classroom activity takes about three hours. It could be less if, after part 1, the students read the article as homework.

Most research articles are written in English, the language of science. If you teach in a school where English is not the language of instruction, you might find it helpful to involve the English teacher in the activity.

To begin with, you need to choose a good research article to use. The following criteria are key:

When selecting the topic, you might like to focus on something covered in the school curriculum. Once you have chosen a topic, you may want to start by searching for research articles published in open-access journals. For example, the Directory of Open Access Journalsw1 (DOAJ), a directory of scientific and scholarly journals published in many languages, is one potential starting point. We would also recommend Biomed Centralw2, a publisher of 220 open-access, online, peer-reviewed journals in biology and medicine. The Public Library of Sciencew3 (PLOS) publishes seven open-access, peer-reviewed journals in biology and medicine. When using these collections, you could search for articles on a specific topic or browse the recent research, featured discussions and / or most viewed sections.

Another source of inspiration could be topics covered in media such as newspapers, popular science magazines like New Scientist or Science News,or their corresponding websites. These websites generally allow you to enter search terms and filter by topic, date and other criteria; some of the articles include suggestions for further reading, such as the original research articles. You will then need to judge whether the research article itself meets the selection criteria listed above.

Research articles on (animal) behaviour or testing medicines often have easy-to-understand experimental procedures. One good example is Computer animations stimulate contagious yawning in chimpanzees (Campbell et al., 2009), which was covered in several newspapers. We chose this article for its length, its appealing content (looking at pictures of yawning chimpanzees makes you yawn yourself), the straightforward experimental procedure and clear scientific claim. From the from the Science in School website, you can download more details of how we used the articlew4.

Let’s begin by looking at the text and the structure of a research article. It starts with a title, which summarises the study and / or its outcome. This is followed by a list of the authors and their affiliations (i.e. who they work for). Usually, the first author is the main researcher and the last author is the head of the department. Then, the dates of submission and publication are given; this shows how long the peer review and revision process has taken. Next, we find the abstract, which summarises the content of the article. The main body of the article starts after the abstract.

In the main body of the article, the first section is the introduction. Here the authors explain the context of the study, i.e. what other researchers have discovered, why this study is important (the gap in knowledge) and what they are going to do. The second section presents the material and methods in enough detail for other scientists to repeat the experiments. In the third section, the results of the study are summarised in text and presented as graphs, diagrams and tables. The fourth section is a discussion of the results. Most importantly, it states the main conclusion (claim), how the evidence supports this conclusion and the implications for further research or for society. After this, you may also find the acknowledgements where the authors thank those who contributed to the research and identify who funded the study. The references section lists all the source materials cited in the article.

To study the textual structure of a research article in class, give each student a copy of the article, and ask him or her to answer some basic questions. By skimming the article to find the answers, your students will quickly become familiar with the structure of the research article and its content. Questions might include:

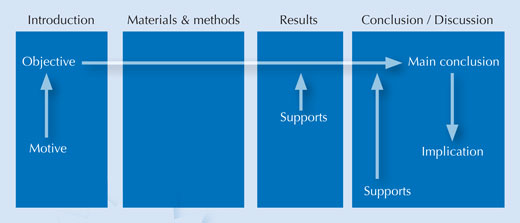

Remember, scientists write research articles to try and convince their peers to accept their scientific claims. This line of reasoning is called the argumentative structure and consists of: the motive (why the study was done), the objective (what was investigated), the main conclusion (the outcome of the study), supports (statements, including data from their own research), references (to previous research and refuted counter-arguments) and one or more implications (which might be a new theory, a new research question, or the impact on society or the research community). Each of these elements is usually found in a specific section of the research article (figure 1).

The next step in the teaching activity is to look at the argumentative structure in more detail. Students could read the whole article in detail, working individually or in small groups to answer guided questions. Next, the answers could be discussed to enhance the students’ understanding.

First, let your students read the introduction, then ask them to answer the following questions:

Next is the materials and methods section. In our experience, students often find this section hard to understand due to its highly technical vocabulary. Therefore, we suggest that you simply explain how the study was performed.

Then, the students can read the results and discussion sections and answer the questions below either as homework or in class. Ask them to:

If your students find it difficult to identify these elements, let them discuss their answers in groups before sharing them with the class. A good visual way of doing this is to create a poster with a structure similar to figure 1. The students can then review their posters in a classroom discussion.

At the end of this classroom activity, you may want to write out the complete argumentative structure of the research article on the board. Finally, encourage your students to discuss whether they agree with the authors’ scientific claim (main conclusion) and to review the article as a whole by playing the role of a reviewer. You could use a role play about peer revieww5, developed by Sense about Science.

There are plenty of media stories about contagious yawning, so this topic would also be ideal for working with news articles. For more details of using news articles in science lessons, see Veneu-Lumb and Costa (2010).

As a follow-up activity, you could ask your students to conduct their own version of the experiment described in the research paper. For example if you used the article we chose, your students could play a yawning video from Youtube (search for ‘contagious yawning’) to another class of students (who did not know what was being tested) and watch how often they yawn. As a control, they could watch a non-yawning video of similar length.

Using the suggested activity for discussing or exploring a few well-chosen research papers with students, teachers can not only deepen their students’ knowledge of the scientific research in question, but also help them to relate more closely to the professional activities of a scientist.

In addition to the questions posed in the article, the teacher could also ask the students to discuss peer review. For example, what is peer review? Why is it done? By how many reviewers? Why is it important (or desirable) that the review process is blind? What is double-blind peer review? The students could also consider the acknowledgements section and discuss how science is financed.

Some interesting follow-up strategies would be to ask students to design their own research project and to write a small research paper. If this were done in two different classes, the students could then review the research papers of the other class, who have investigated the same or a similar topic.

Which science lessons and which age groups to target with the activity would depend on the research paper chosen by the teacher. However, the strategy would be most useful for upper-secondary-level students (ages 15-18). The fact that most research papers are in English should not be seen as an obstacle, but as an opportunity to implement interdisciplinary projects with language teachers.

Betina da Silva Lopes, Portugal