Alan Leshner: at the interface of science and society Inspire article

Dr Alan Leshner, Chief Executive Officer of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and Executive Publisher of the renowned Science magazine, tells Marlene Rau and Sonia Furtado about his varied career and shares his views on science education issues.

Image courtesy of AAAS

Alan Leshner started his career as a neuroscientist at a time when neuroscience still fell under the umbrella of psychology. “Like many people,” he says, “I became a scientist because of an individual mentor. I was always genuinely interested in science and thought I would become a physician. But at university I started to do some research with one of my psychology professors, and I fell in love with the process of research and scientific inquiry. So instead of enrolling in medical school after my degree, I did neuroscience.

“There was no such thing as a neuroscientist back then, though: in the late 1960s, if you were interested in the brain, or in the relationship between biology and behaviour, you went into psychology. However, I was part of a first generation of doctoral students who were trained in both psychology and physiology – and in my case, endocrinology, too.”

When asked to point out the most interesting aspect of his scientific research, Dr Leshner is reticent – he’d rather talk of the wider scope of his research than focus on a particular detail: “I spent twelve years as a bench scientist, so there is no single thing that stands out, but – like many people – I am interested in grand, overarching questions about the nature of the relationship between biology and behaviour. What I did was approach that through an unusual question. While most people asked ‘how does the brain come to generate a mind?’, I was interested in how other biological systems can modify or affect behaviour, and became interested in hormones. Not in the traditional area of interest at the time – sex hormones and sexual behaviour – I was interested in the role of hormones in controlling what were then called regulatory behaviours: eating, exercising and things like that. Later I became interested in how hormones could affect social behaviours and mood; specifically in the role of the hormones of the adrenal gland on aggressive versus submissive behaviour, and in what came to be called premenstrual tension and how hormones could be involved in that.”

Author of a textbook on hormones and behaviour (Leshner, 1978), Dr Leshner doesn’t think current knowledge of behaviour can provide any great insights into how to manage a classroom, but he does believe it could be a very useful resource to help get youngsters interested in science. “There is a whole body of literature on the biology of behaviour that I think would be both very exciting and very stimulating to young people”, he says.

iStockphoto

“Unsurprisingly, many young people are very interested in their own hormones and their effects. In addition to that, most people are intrigued by their mind and their own behaviour. If you can give them insights into the phenomena that relate to them, that’s a very good way to engage people with science generally. I’m fond of saying most people are interested in their brains because they’re interested in their minds. This makes studying the brain fascinating, because people think it will give them insight into their minds, into their self, into their individuality.”

What about the difference between mind and brain? Regardless of what people may think, scientists are certain there is none. Dr Leshner states: “Within the scientific community it’s not a question anymore. It may be one in the broader society, but scientists agree that your mind is not floating around outside your body or in your liver – it’s in your head. You don’t have a separate mind and brain. That doesn’t mean you don’t have a mind or you don’t experience your own consciousness, but the mechanism that generates it is in the mush inside that hard thing that sits above your shoulders. It’s very hard for people to accept that, but that’s what we’ve learned over the course of the last fifty years.”

Although he is still interested in these matters, Dr Leshner’s career has moved away from the lab bench. How did he go from researching behaviour to working in science policy? “Well, I was asked,” he replies. “I’ve always been interested in the relationship between biology and things like mental disorders, mood and emotion. So although my research was very focused, I was always interested in the kind of broader questions that might interest society at large. I was asked to go to the National Science Foundationw1 for a year, in one of their rotating programme officer positions. Those are jobs where you give out grants, and I did that in a programme called ‘psychobiology’. While I was there, I got involved in other projects that were more policy-related, and they asked me to stay for another year to work on a big science policy report called ‘The five year outlook on science and technology’. I liked it, and they asked me to stay another year. I kept my appointment at Bucknell Universityw2, so I kept my lab going during that time. Then, by accident, I was invited to a meeting about a new science education commission that the National Science Boardw3 was establishing at the National Science Foundation. There they asked me if I would come and work on the staff, and I became deputy director of that commission. So I spent a couple of years working on science education at elementary- and secondary-school levels. I had eight jobs in nine years at the National Science Foundation,” Alan Leshner admits. “But they were good,” he adds. “Each one was better than the one before.

/iStockphoto

“After that, I was asked to become the deputy director of the National Institute of Mental Healthw4, at the National Institutes of Health. I did that for a couple of years, and then the director left and I became the acting director of the institute for another couple of years. Then I was asked if I wanted to become the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)w5, also at the National Institutes of Health. I thought: ‘Oh, that’s an interesting challenge. There is no science behind the way in which society deals with drug abuse and addiction, and I could do something about that.’ So I was the NIDA director for almost eight years. But because everything comes full circle, I was eventually asked if I wanted to come back to my broader scientific roots and work at AAASw6 and Science magazinew7. I figured I had done about as much as I could do in drug abuse, and maybe I would be able to have a broader effect on the science–society relationship by coming to AAAS, so that’s how I got here.

Actually my whole career is an accident. I was lucky: my parents didn’t think it was essential that I have a plan.”

His latent interest in the interface between science and society was sparked into action during his time at the National Institute of Mental Health, Dr Leshner says. “At the time, universities and high schools were teaching that diseases like schizophrenia were caused by early parental experience. You know, we had words like ‘refrigerator parents’ or ‘schizophrenogenic mothers’ – mothers that induced schizophrenia. I was in a room with four people when we decided we needed to tell the world that schizophrenia was a brain disease. So we mounted a major public information campaign, along with a patient group called ‘The national alliance for mental illness’. We successfully used science to change public understanding of mental illness, so that now if you say ‘schizophrenogenic mothers’, everybody laughs. If you say your mother made you schizophrenic, people think it’s a joke; everybody knows it’s a brain disease. Well, we had to tell people, using the science.”

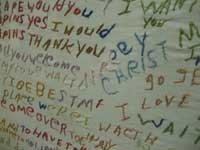

an insight into her mind with a

cloth she embroidered, an exhibit

at the Glore Psychiatric Museum,

St Joseph, Missouri, USA

Image courtesy of cometstarmoon;

image source: Wikimedia Commons

At AAAS, Alan Leshner now looks beyond his initial field of interest, to more general tensions between science and society. “The link between science and the rest of society is a little fragile these days,” he says. “It’s fragile in part because people don’t understand what is and isn’t science, and in part because science is encroaching on areas of core human values, like who we are. There are other kinds of issues that have political or economic ramifications, like what to do about global warming. We have a lot of work to do, getting science and society on the same page and going in the same direction.”

Nevertheless, Leshner has pretty clear ideas as to how that link can be strengthened: “I believe in public engagement with science: that is in dialogue, communication, bringing scientists and the rest of the public together to work on common issues, listening to each other. One of the hardest things is to get scientists to listen to the public, but every time they do, they benefit tremendously from it.”

Dr Leshner believes that educating the public is of paramount importance, preferably from an early age, but that the challenges faced by current educational systems are still very similar to those he encountered while in the science education commission at the National Science Foundation. “I think the issues were actually the same back then as they are today, and that’s very discouraging. We have not made tremendous progress. For instance, we still can’t get agreement on the standards and objectives for what we want taught at the different pre-college levels in science, mathematics and technology

“And I believe that the single biggest problem is that in the US, we don’t pay science teachers enough to keep them in the business. The best and brightest science teachers frequently get discouraged, both by the bureaucracy of our educational systems and by the terrible pay.

/ iStockphoto

“Therefore, after teaching for a while, they feel as if they need to move to other fields. I believe that until the nations of the world recognise and respect teachers for the very important and difficult jobs that they do, we’ll never really solve the so-called science education problems. I actually think if we were to pay teachers reasonably, teaching in secondary or even elementary schools would be viewed as an extremely productive career choice for scientists. There is nothing that says all scientists have to work at the bench.

“Scientific training can be used in a wide variety of ways, and teaching is among the most noble things you can do in the world. So I would applaud people who choose to use their science education to become teachers. I just think it’s very difficult to get them to do that.”

The man who once said “People still respect science and technology, but they have no idea what science is” believes school could play a fundamental role in changing this state of affairs. “You can’t teach science in a vacuum, but if you don’t focus on the nature of the enterprise, you get lost in the details. So you have to find a way to do both. One such way is to start with a societal issue such as global warming and then ask ‘How did science teach us about it?’ How do we know Earth is warming? It’s not just that the graph shows it. It’s a whole process by which we’ve made those advances in understanding.

“You can either teach the graph, or you can teach the process of generating and understanding the graph – and of understanding a bad graph – you know, what makes something true or false for science. Then people could discriminate better between what is and isn’t science. The assertion that astrology or homoeopathy or creationism are scientific should be dependent on one’s ability to prove that they use scientific methodology, that the results are reproducible and that the findings are observable: all of the normal criteria that make something scientific. The fact that three scientists believe something doesn’t make it scientific.”

Finally, after holding so many different positions and being involved in so many different areas, what would Alan Leshner like to do next? “Oh, I sort of like this. I think representing the scientific community is a noble thing to do, and anything that I can do to help keep the relationship between science and the rest of society smooth is very rewarding. My main interest is that interface between science and the rest of society, and what better way to work on that than to be the head of an organisation whose mission is to advance science and serve society?”

References

- Leshner A (1978) An Introduction to Behavioral Endocrinology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780195022667

Web References

- w1 – For more information on the US National Science Foundation, see: www.nsf.gov

- w2 – To learn more about Bucknell University, USA, see: www.bucknell.edu

- w3 – Find out more about the US National Science Board on their website: www.nsf.gov/nsb

- w4 – Learn more about the National Institute for Mental Health at the US National Institutes of Health here: www.nimh.nih.gov

- w5 – For more information on the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), see: www.nida.nih.gov

- The NIDA also provides teaching material for neuroscience and drug abuse education in English and Spanish: www.drugabuse.gov/parent-teacher.html

- w6 – Find out more about the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) here: www.aaas.org

- w7 – You can find the website of the Science magazine here: www.sciencemag.org

Resources

- For an article on the role of one particular hormone, oxyntomodulin, on eating behaviour, see: Wynne K, Bloom S (2007) Oxyntomodulin: a new therapy for obesity? Science in School 6: 25-29.

- To find out more about Euroscience, the European counterpart of AAAS, and its activities, see: www.euroscience.org

Review

This article on an atypical career in science can be used to discuss science and society issues in class, including: Are teachers paid enough or too much? Do you think it matters if people don’t know what is and isn’t science? What are the important scientific issues that have moral, political or economic ramifications?

Halina Stanley, France