The LHC: a look inside Understand article

In the second of two articles, Rolf Landua from CERN takes us deep below the ground to visit the largest scientific endeavour on Earth – the Large Hadron Collider and its experiments.

The accelerator

technicians used various means

of transport to move around the

27 km tunnel. Alongside the

technician, two LHC magnets can

be seen, before they were

connected together. The blue

cylinders contain the magnetic

yoke and coil of the dipole

magnets, together with the liquid

helium system required to cool

the magnet so that it becomes

superconducting

Image courtesy of CERN

The Large Hadron Colliderw1 (LHC) at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) is a gigantic scientific instrument spanning the Swiss-French border near Geneva, Switzerland. The world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator, it is used by almost 10 000 physicists from more than 80 countries to search for particles to unravel the chain of events that shaped our Universe a fraction of a second after the Big Bang. It could resolve puzzles ranging from the properties of the smallest particles to the biggest structures in the vastness of the Universe.

The design and construction of the LHC took about 20 years at a total cost of €3.6 billion. It is housed in a 27 km long and 3.8 m wide tunnel about 100 m underground. At this level, there is a geologically stable stratum, and the depth prevents any radiation from escaping. Until 2000, the tunnel was the home of the Large Electron-Positron (LEP) storage ring, which was built in 1989. This earlier accelerator collided electrons with their anti-particles, positrons (for an explanation of antimatter, see Landua & Rau, 2008), to study the properties of the resulting particles and their interactions with great precision.

There are eight elevators leading down into the tunnel, and although the ride is only one stop, it takes a whole minute. To move between the eight access points, maintenance and security people use bicycles to move around the tunnel – sometimes for several kilometres. The LHC is automatically operated from a central control centre, so once the experiments have started, engineers and technicians will only have to access the tunnel for maintenance.

The actual experiment is a rather simple process: the LHC will collide two hadrons – either protons or lead nuclei – at close to the speed of light. The very high levels of energy involved will allow the kinetic energy of the colliding particles to be transformed into matter, according to Einstein’s law E=mc2, and all matter particles created in the collision will be detected and measured. This experiment will be repeated up to 600 million times per second, for many years. The LHC will mainly perform proton-proton collisions, which will be studied by three of its four detectors (ATLAS, CMS, and LHCb). However, for several weeks per year, heavy ions (lead nuclei) will be accelerated and collided instead, to be studied mainly by the dedicated ALICE detector.

accelerator with its three main

components: the beam pipes,

the acceleration elements, and

the bending magnets.

Click to enlarge image

Image courtesy of DESY

Like any other particle accelerator, the LHC has three main components: the beam pipes, the accelerating structures, and the magnet system (see diagram). Inside its two beam pipes, each 6.3 cm in diameter, proton (or heavy ion) beams travel in opposite directions (one direction in each pipe) in an ultra-high vacuum of 10-13 bar, comparable to the density of matter in outer space. This low pressure is necessary to minimise the number of collisions with resting gas molecules and the subsequent loss of the accelerated particles.

The protons are supplied from a hydrogen gas bottle. Hydrogen atoms consist of a proton and an electron. Scientists remove the electrons using an electric discharge, after which the protons are guided towards the accelerator through electric and magnetic fields. For the LHC beam, 300 trillion protons are required, but since a single cubic centimetre of hydrogen gas at room temperature contains about 60 million trillion protons, the LHC can be refilled 200 000 times with just one cubic centimetre of gas – and it only needs refilling twice a day!

The second part of an accelerator consists of its accelerating structures. Before protons (or heavy ions) are introduced into the two LHC beam pipes, they are accelerated in smaller accelerators (connected to the LHC) to about 6 % of their final energy. Inside the LHC, the particles acquire their final energy from eight accelerating structures (accelerator cavities).

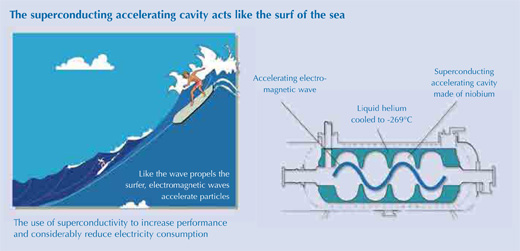

Every time the particles run through these cavities, they are accelerated by a strong electric field of about 5 MV/m. The functionality of the accelerators is comparable to surf on the sea (see diagram below): a bunch of protons, about 100 billion of them – the surfers – ride together on an enormous electromagnetic wave and gain kinetic energy. Each wave accelerates one bunch of protons, and each of the two beams consists of 2800 discrete bunches, one every seven metres. After 20 minutes, they reach their final energy, while doing 11 245 circuits of the LHC ring per second. In those 20 minutes, the protons cover a distance further than from Earth to the Sun and back.

Image courtesy of CERN

They enter the LHC at 99.9997828 % of the speed of light. After acceleration, they reach 99.9999991 %. This is about the maximum speed that can be reached, since nothing can move faster than light, according to the theory of relativity. Although it might seem like an insignificant gain in speed, at close to the speed of light, even a small acceleration results in a large gain in mass, and this is the important part. A motionless proton has a mass of 0.938 GeV (938 million electron volts). The accelerators bring them to a final mass (or energy, which in this case is practically the same thing) of 7000 billion electron volts (7 tera-eV or 7 TeV). If you could – hypothetically – accelerate a person of 100 kg in the LHC, his or her mass would end up being 700 t.

of an LHC dipole magnet shows

some of the parts vital for the

operation of these components.

The magnets must be cooled to

1.9 K so that the superconducting

coils can produce the required 8 T

magnetic field.

Click to enlarge image

Image courtesy of CERN

Without external forces, the protons would fly in a straight line. To give them a circular trajectory, the pipes are surrounded by a large magnet system that deflects the protons’ path – these magnets are the third part of every particle accelerator. The larger the mass of a particle becomes, the stronger the magnets need to be to keep it on track. This is where the limitations of a particle accelerator lie, since at a certain magnetic energy, the material of the magnetic coils cannot resist the forces of its own magnetic field anymore. The magnets used in the LHC have been specially designed: the dominant part of the magnet system consists of 1232 dipole magnets, each with a length of about 16 m and a weight of 35 t, which create a maximum magnetic field of 8.33 tesla – 150 000 stronger than Earth’s magnetic field.

The magnets have a special two-in-one design: they contain two magnet coils on the inside, each surrounding one of the two beam pipes. The current runs through the coils to create two magnetic fields, pointing downwards in one pipe and upwards in the other. This is how two particles (protons or lead nuclei) of the same charge can follow the same track in opposite directions – one in each beam pipe.

In addition to the dipole magnets, there are quadrupole magnets (with four magnetic poles) for focusing the beams, and thousands of additional smaller sextupole and octupole magnets (with six or eight magnetic poles each, respectively) for correcting the beam size and position.

All magnet coils and the accelerator cavities are built from special materials (niobium and titanium) that become superconducting at very low temperatures, conducting electricity to produce the electric and magnetic fields without resistance. To reach their maximum performance, the magnets need to be chilled to -271.3°C (1.9K) – a temperature colder than outer space. To cool the magnets, much of the accelerator is connected to a distribution system of liquid nitrogen and helium (see box). Just one-eighth of the LHC’s cryogenic distribution system would qualify as the world’s largest fridge.

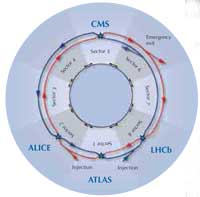

Around the ring are four points at which the chain of magnets is broken: they contain the four huge caverns for the LHC experiments and their detectors. Here, the trajectories of the inner and outer beams are made to cross each other and swap places in special X-shaped beam pipes. In all four X-shaped pipes, the beams cross at an angle of 1.5 degrees, allowing the beams to be brought into collision.

Click to enlarge image

Image courtesy of Nicola Graf

Huge detectors – described below – surround the collision points. To increase the probability of particle collisions, the bunches of particles are squeezed, by special magnets just in front of each collision chamber, to a diameter of 16 µm – thinner than a human hair – and 80 mm in length. The beams are so tiny that the task of making them collide is akin to firing needles from two positions 10 km apart with such precision that they meet halfway! However, the LHC technology manages this intricate task. Nonetheless, even in these focused beams of particles, the density is still very low – 100 million times lower than that of water – so most of the particles pass straight through the other bunch of particles without colliding or even slowing down. Thus, although there are 100 billion protons in each bunch, when two bunches collide, only about 20 particle collisions occur. Since collisions between two bunches occur 31 million times per second (2800 bunches x 11 245 turns of the LHC ring per second), this still gives about 600 million proton collisions per second when the LHC is operating at maximum intensity.

A single bunch of protons travelling at full speed has the same kinetic energy as a one-tonne elephant running at 50 km/h, and the entire energy contained in the beam is 315 megajoules (MJ), enough to melt nearly 500 kg of copper. Therefore, considerable efforts have gone into the security of the LHC. Should the beam become unstable, this will be immediately detected by the beam sensors, and within the next three laps around the ring (i.e. in less than a thousandth of a second) the beam will be deflected into a kind of emergency exit, where it is absorbed by graphite plates and concrete before it can cause any further damage.

The experiments

The LHC will collide two protons at a total kinetic energy of 7 + 7 = 14 TeV (or two lead ions at a total energy of 1140 TeV), and then detect and measure the new particles produced when the kinetic energy is transformed into matter.

According to quantum physics, these collisions will generate all particles of the standard model (as described in Landua & Rau, 2008) with certain probabilities. However, the probability of generating the heavy particles that scientists are actually looking for is very low. Few of the particle collisions will be hard enough to produce new, heavy particles. Theory predicts that Higgs bosons (to learn more about the Higgs boson, see Landua & Rau, 2008) or other completely new phenomena that are being searched for will be produced only very rarely (typically once in 1012 collisions), so it is necessary to study many collisions in order to find the ‘needle in a million haystacks’. That is why the LHC will be run for many years, 24 hours a day.

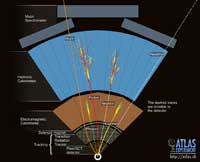

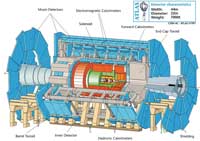

The events (an event is a collision with all its resulting particles) are studied using giant detectors that are able to reconstruct what happened during the collisions – and to keep up with the enormous collision rates. Detectors can be compared to huge three-dimensional digital cameras that can take up to 40 million snapshots (with digitised information from tens of millions of sensors) per second. The detectors are built in layers, and each layer has a different functionality (see diagram below). The inner ones are the least dense, while the outer ones are denser and more compact.

the ATLAS detector, showing the

different layers and the passage

of different particle types through

the layers.

Click to enlarge image

Image courtesy of CERN

The heavy particles that scientists hope to produce in the LHC collisions are predicted to be very short-lived, rapidly decaying into lighter, known particles. After a hard collision, hundreds of these lighter particles, for example electrons, muons and photons, but also protons, neutrons and others, fly through the detector at close to the speed of light. Detectors use these lighter particles to deduce the brief existence of the new, heavy ones.

The trajectories of charged particle are bent by magnetic fields, and their radius of curvature is used to calculate their momentum: the higher the kinetic energy, the shallower the curvature. For particles with high kinetic energy, therefore, a sufficiently long trajectory must be measured in order to accurately determine the curvature radius. Other important parts of a detector are calorimeters for measuring the energy of particles (both charged and uncharged). The calorimeters too have to be large enough to absorb as much particle energy as possible. These are the two principle reasons why the LHC detectors are so large.

The detectors are built to hermetically enclose the interaction region in order to account for the total energy and momentum balance of each event and to reconstruct it in detail. Combining the information from the different layers of the detector, it is possible to determine the type of particle which has left each trace.

Charged particles – electrons, protons and muons – leave traces through ionisation. Electrons are very light and therefore lose their energy quickly, while protons penetrate further through the layers of the detector. Photons themselves leave no trace, but in the calorimeters, each photon converts into one electron and one positron, the energies of which are then measured. The energy of neutrons is measured indirectly: neutrons transfer their energy to protons, and these protons are then detected. Muons are the only particles that reach (and are detected by) the outermost layers of the detector (see diagram above).

Each part of a detector is connected to an electronic readout system via thousands of cables. As soon as an impulse is registered, the system records the exact place and time and sends the information to a computer. Several hundred computers work together to combine the information. At the top of the computer hierarchy is a very fast system which decides – in a split second – whether an event is interesting or not. There are many different criteria to select potentially significant events, which is how the enormous data of 600 million events is reduced to a few hundred events per second that are investigated in detail.

The LHC detectors were designed, constructed and commissioned by international collaborations, bringing together scientists from institutes all over the world. In total, there are four large (ATLAS, CMS, LHCb and ALICE) and two small (TOTEM, LHCf) experiments at the LHC. Considering that it took 20 years to plan and construct the detectors, and they are intended to run for more than 10 years, the total duration of the experiments is almost equivalent to the entire career of a physicist.

The construction of these detectors is the result of what could be called a ‘group intelligence’: while the scientists working on a detector understand the function of the apparatus in general, no one scientist is familiar with the details and precise function of each single part. In such a collaboration, every scientist contributes with his or her expertise to the overall success.

ATLAS and CMS

largest of its type in the world

when its construction is completed;

the people in the diagram are to

scale. Click to enlarge image

Image courtesy of CERN

The two largest experiments, ATLASw2 (A Toroidal LHC ApparatuS) and CMSw3 (Compact Muon Solenoid), are general-purpose detectors optimised for the search for new particles. ATLAS and CMS are located on opposite sides of the LHC ring, 9 km apart (see diagram of the experiments). Having two independently designed detectors is vital for cross-confirmation of any new discoveries.

The ATLAS and the CMS collaborations each consist of more than 2000 physicists from 35 countries.The ATLAS detector has the shape of a cylinder 25 m in diameter and 45 m in length, about half as big as Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, France, and weighing the same as the Eiffel Tower (7000 t). Its magnetic field is produced by a solenoid in the inner part and an enormous doughnut-shaped toroid magnet further outside (seediagram, right).

The CMS detector also has a cylindrical shape (15m in diameter and 21m in length) and is built around a superconducting solenoid magnet generating a field of 4 tesla, which is confined by a steel yoke that forms the bulk of the detector’s weight of 12 500 t. While ATLAS was constructed in situ, the CMS detector was constructed at the surface, lowered underground in 15 sections and then assembled.

LHCb

The LHCbw4 experiment will help us to understand why we live in a universe that appears to be composed almost entirely of matter but no antimatter. It specialises in investigating the slight differences between matter and antimatter by studying a type of particle called the bottom quark, or b quark (see Landua & Rau, 2008, for an explanation of antimatter and quark types). To identify and measure the b quarks and their antimatter counterparts, the anti-b quarks, LHCb has sophisticated movable tracking detectors close to the path of the beams circling in the LHC.

Image courtesy of CERN

ALICE

ALICEw5 (A Large Ion Collider Experiment) is a specialised detector for analysing the collisions of lead ions. For a few weeks each year these, rather than protons, will be collided in the LHC. Within the dimensions of an atomic nucleus, this will create conditions that prevailed about a millionth of a second after the Big Bang, when the temperature of the entire Universe was about 100 000 times hotter than the interior of the Sun. These conditions might create a state of matter called a quark-gluon plasma, the characteristics of which physicists hope to study (for a further explanation of the quark-gluon plasma, see Landua, 2008).

The data challenge

The LHC will produce roughly 15 petabytes (15 million gigabytes) of data annually – enough to fill more than 3 million DVDs. Thousands of scientists around the world want to access and analyse these data, so CERN is collaborating with institutions in 33 countries to operate a distributed computing and data storage infrastructure: the LHC Computing Grid (LCG).

The LCG will allow data from the LHC experiments to be distributed around the globe, with a primary backup kept at CERN. After initial processing, the data will be distributed to eleven large computer centres. These tier-1 centres will make the data available to more than 120 tier-2 centres for specific analysis tasks. Individual scientists can then access the LHC data from their home country, using local computer clusters or even individual PCs.

Who works on the LHC?

Liz Gregson from Imperial College London, UK, talks to some of the CERN employees.

Katharine Leney, ATLAS physicist

Katharine is doing a PhD in physics on the search for the Higgs boson, working on the ATLAS detector. She is also developing a tool to look at conditions within the detector, to ensure that the data obtained will be usable. “It’s a really exciting time to be here, working alongside some of the world’s top physicists.” In addition to her research, she has recently become a CERN guide, showing visitors the experiments and explaining the work that scientists do there.

Dr Marco Cattaneo, project co-ordination

Image courtesy of CERN

Marco was born in Italy and moved to the UK at the age of ten. Today he lives in France, works in Switzerland, and has a Swiss-British wife and two children who can speak three languages fluently. “When asked what I am, I can only answer European!” he says. He has been at CERN since 1994. He is deputy project leader on the software and computing project for the LHCb experiment. His main job is to co-ordinate the work of around 50 physicists who develop software that enables reconstructions of the original trajectories of the particle collisions recorded by the detector. This is then integrated into a single reconstruction programme, so that others can study the characteristics of the collision event.

Marco enjoys the work atmosphere at CERN: “It attracts about 50 percent of the world’s particle physics community, meaning that the vast majority of people working at CERN are highly skilled in their field and very motivated by their work. It is not unusual to be on first-name terms with Nobel laureates.”

This text was first published in the Imperial College London alumni magazine, Imperial Matters.

As we go to press: a helium leak in the LHC

At mid-day on 19 September 2008, nine days after start-up, an incident occurred in one of the eight sectors (sector 3-4) of the LHC. The cause was a faulty superconducting electrical connection between two of the LHC magnets. When the electrical current increased above 9000 A, part of the cable developed an electrical resistance which resulted in a large release of resistive electric power in the cable. Within one second, an electrical arc punctured the helium enclosure and released more than one tonne of liquid helium into the insulation vacuum of the cooling system. Since several magnets share a common insulation vacuum, the resulting large increase in pressure led to mechanical damage of up to 24 dipole magnets and 5 quadrupole magnets.

As we go to press, sector 3-4 has been warmed up so that repairs can take place. At least 29 magnets will have to be taken out, brought to the surface, repaired and tested, then re-installed and re-connected. The beam pipes will have to be carefully cleaned as well. While these repairs would take not more than a few weeks in a conventional particle accelerator, the complexity of the superconducting installations of the LHC requires several months of work, plus about six weeks to cool the magnets in this sector back down to a temperature of 1.9 K. It is foreseen that the LHC will be restarted and carry out its first collisions in 2009.

References

- Landua R, Rau M (2008) The LHC: a step closer to the Big Bang. Science in School 10: 26-33.

Web References

- w1 – A guide to the Large Hadron Collider can be found here: http://cdsweb.cern.ch/record/1092437/files/CERN-Brochure-2008-001-Eng.pdf

- A video of the Large Hadron Rap can be viewed here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=j50ZssEojtM

- w2 – For more information on the ATLAS experiment, see: http://atlas.ch

- w3 – For more information on the CMS experiment, see: http://cms.web.cern.ch

- w4 – For more information on the LHCb experiment, see: http://lhcb-public.web.cern.ch/lhcb-public

- w5 – For more information on the ALICE experiment, see: http://aliceinfo.cern.ch/Public/Welcome.html

Resources

- A much more detailed account of the standard model and the LHC experiments can be found in Rolf Landua’s German-language book:

- Boffin H (2008) “Intelligence is of secondary importance in research”. Science in School 10: 14-19.

- Warmbein B (2007) Making dark matter a little brighter. Science in School 5: 78-80.

- The CERN website devotes a substantial amount of space to the LHC; see: http://public.web.cern.ch/public/en/LHC

- The CERN pages offer a wealth of teaching material on particle physics and accelerators: http://education.web.cern.ch/education/Chapter2/Intro.html

- The LHC UK website includes materials about the LHC for teachers and students: www.lhc.ac.uk